State Water Resources Control Board

Division of Water Quality

P.O. Box 100 Sacramento, California 95812-0100

Fax: 916-341-5620 email: commentletters@waterboards.ca.gov

GEOGRAPHICAL SCALE OF SMALL-SCALE SUCTION DREDGING

It has been observed that environmentalists opposing suction dredging use data gleaned from reports that studied effects of environmental perturbations that are occurring on a system-wide basis. For example, they would characterize the affects of turbidity from a suction dredge as if it would impact downstream organisms in a manner that system-wide high water flow events might. This approach is entirely inconsistent with the way in which suction dredges operate or generally impact their downstream environment.

The California Department of Fish and Game (1997) described typical dredging activities as follows’ “An individual suction dredge operation affects a relatively small portion of a stream or river. A recreational suction dredger (representing 90-percent of all dredgers) may spend a total of four to eight hours per day in the water dredging an area of 1 to 10 square meters. The average number of hours is 5.6 hours per day. The remaining time is spent working on equipment and processing dredged material. The area or length of river or streambed worked by a single suction dredger, as compared to total river length, is relatively small compared to the total available area.”

In the Oregon Siskiyou National Forest Dredge Study, Chapter 4, Environmental Consequences, some perspective is given to small-scale mining. “The average claim size is 20 acres. The total acreage of all analyzed claims related to the total acres of watershed is about 0.2 percent. The average stream width reflected in the analysis is about 20 feet or less and the average mining claim is 1320 feet in length. The percentage of land area within riparian zones on the Siskiyou National Forest occupied by mining claims is estimated to be only 0.1 percent.” The report goes on to say, “Over the past 10 years, approximately 200 suction dredge operators per season operate on the Siskiyou National Forest” (SNF, 2001).

A report from the U.S. Forest Service, Siskiyou National Forest (Cooley, 1995) answered the frequently asked question, “How much material is moved by annual mining suction dredge activities and how much does this figure compare with the natural movement of such materials by surface erosion and mass movement?” The answer was that suction dredges moved a total of 2,413 cubic yards for the season. Cooley (1995) used the most conservative values and estimated that the Siskiyou National Forest would move 331,000 cubic yards of material each year from natural causes. Compared to the 2413 (in-stream) cubic yards re-located by suction mining operations the movement rate by suction dredge mining would equal about 0.7% of natural rates.

It has been suggested that a single operating suction dredge may not pose a problem but the operation of multiple dredges would produce a cumulative effect that could cause harm to aquatic organisms. However, “No additive effects were detected on the Yuba River from 40 active dredges on a 6.8 mile (11 km) stretch. The area most impacted was from the dredge to about 98 feet (30 meters) downstream, for most turbidity and settelable solids (Harvey, B.C., K. McCleneghan, J.D. Linn, and C.L. Langley, 1982). In another study, “Six small dredges (<6 inch dredge nozzle) on a 1.2 mile (2 km) stretch had no additive effect (Harvey, B.C., 1986). Water quality was typically temporally and spatially restricted to the time and immediate vicinity of the dredge (North, P.A., 1993).

A report on the water quality cumulative effects of placer mining on the Chugach National Forest, Alaska found that, “The results from water quality sampling do not indicate any strong cumulative effects from multiple placer mining operations within the sampled drainages.” “Several suction dredges probably operated simultaneously on the same drainage, but did not affect water quality as evidenced by above and below water sample results. In the recreational mining area of Resurrection Creek, five and six dredges would be operating and not produce any water quality changes (Huber and Blanchet, 1992).

The California Department of Fish and Game stated in its Draft Environmental Impact Report that “Department regulations do not currently limit dredger densities but the activity itself is somewhat self-regulating. Suction dredge operators must space themselves apart from each other to avoid working in the turbidity plume of the next operator working upstream. Suction Dredging requires relatively clear water to successfully harvest gold ” (CDFG, 1997).

ELEVATED TURBIDITY

Suction dredging causes less than significant effects to water quality. The impacts include increased turbidity levels caused by re-suspended streambed sediment and pollution caused by spilling of gas and oil used to operate suction dredges (CDFG, 1997).

“Suction dredges, powered by internal combustion engines of various sizes, operate while floating on the surface of streams and rivers. As such, oil and gas may leak or spill onto the water’s surface. There have not been any observed or reported cases of harm to plant or wildlife as a result of oil or gas spills associated with suction dredging” (CDFG, 1997).

The impact of turbidities on water quality caused by suction dredging can vary considerably depending on many factors. Factors which appear to influence the degree and impact of turbidity include the amount and type of fines (fine sediment) in the substrate, the size and number of suction dredges relative to stream flow and reach of stream, and background turbidities (CDFG, 1997).

Because of low ambient levels of turbidity on Butte Creek and the North Fork American River, California, Harvey (1986) easily observed increases of 4 to 5 NTU from suction dredging. Turbidity plumes created by suction dredging in Big East Fork Creek were visible in Canyon Creek 403 feet (123 meters) downstream from the dredges (Somer and Hassler, 1992).

In contrast, Thomas (1985), using a dredge with a 2.5-inch diameter nozzle on Gold Creek, Montana, found that suspended sediment levels returned to ambient levels 100 feet below the dredge. Gold Creek is a relatively undisturbed third order stream with flows of 14 cubic feet per second. A turbidity tail from a 5-inch (12.7 cm) dredge on Clear Creek, California was observable for only 200 feet downstream. Water velocity at the site was about 1 foot per second (Lewis, 1962).

Turbidity below a 2.5 inch suction dredge in two Idaho streams was nearly undetectable even though fine sediment, less than 0.5 mm in diameter, made up 13 to 18 percent, by weight, of substrate in the two streams (Griffith and Andrews, 1981).

“During a dredging test carried out by the California Department of Fish and Game on the north fork of American River, it was concluded that turbidity was greatest immediately downstream, returning to ambient levels within 100 feet. Referring to 52 dredges studied, Harvey (1982) stated “…generally rapid recovery to control levels in both turbidity and settable solids occurred below dredging activity.”

Hassler (1986) noted “…during dredging, suspended sediment and turbidity were high immediately below the dredge, but diminished rapidly within distance downstream.” He measured 20.5 NTU 4 meters below a 5-inch dredge that dropped off to 3.4 NTU 49 meters below the dredge. Turbidity from a 4-inch dredge dropped from 5.6 NTU 4 meters below to 2.9 NTU 49 meters below with 0.9 NTU above. He further noted “…water quality was impacted only during the actual operation of the dredge…since a full day of mining by most Canyon Creek operators included only 2 to 4 hours of dredge running time, water quality was impacted for a short time.” Also “…the water quality of Canyon Creek was very good and only affected by suction dredging near the dredge when it was operated.”

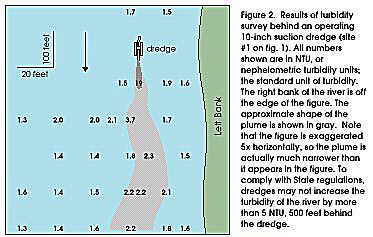

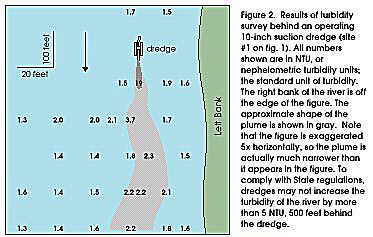

The US Geological Survey and the Alaska Department of Natural Resources conducted a survey into dredging on Alaska’s Fortymile River, which is a river designated as a wild and scenic corridor. The study stated, “One dredge had a 10-inch diameter intake hose and was working relatively fine sediment on a smooth but fast section of the river. The other dredge had an 8-inch intake and was working coarser sediments in a shallower reach of the river. State regulations require that suction dredges may not increase the turbidity of the river by more than 5 nephelometric turbidity units (NTU), 500 feet (=150m) downstream. In both cases, the dredges were well within compliance with this regulation.”

http://www.akmining.com/mine/usgs1.htm

Samples were collected on a grid extending downstream from the dredges as they were operating and compared to measurements made upstream of the dredges. One dredge had a 10-inch diameter intake hose and was working relatively fine sediments on a smooth but fast section of the river. The results of the turbidity survey for the 10-inch dredge are shown on figure 2. Turbidity values behind the 8-inch dredge were lower, because the smaller intake was moving less sediment material, and because the coarser sediments being worked by the 8-inch dredge settled more rapidly.

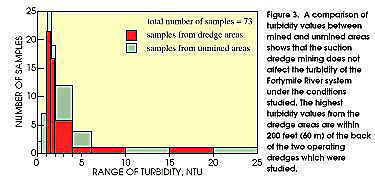

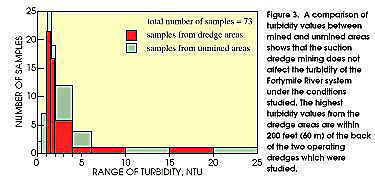

The turbidity values found in the dredge studies fall within the range of turbidity values found for currently mined areas of the Fortymile River and many of its un-mined tributaries. Figure 3 shows the ranges of turbidity values observed along the horizontal axis, and the number of samples that fall within each of those ranges. For example, 25 samples had turbidity between 1.0 and 1.5 NTU, 22 of which were in a dredged area. The highest turbidity value was from an un-mined tributary to Uhler Creek; the lowest from a number of different tributaries to the North Fork. As seen on the figure, there is no appreciable difference in the distribution of turbidity values between mined and un-mined areas.

http://www.akmining.com/mine/usgs1.htm

In American studies, average turbidity levels have been shown to be between 5 and 15 NTU 5 meters below dredges. But even the maximum turbidity level measured in a clay pocket (51 NTU) fell below 10 NTU within 45 meters. Turbidity increases, from even large dredges on moderate sized streams, have shown to be fairly low, usually 25 NTU or less, and to return to background within 30 meters. The impact is localized and short lived; indicating minimum impact on moderate and larger waterways.

Within any waterway, sediment is primarily carried in suspension during periods of rainfall and high flow. This is an important point, as it indicates that a dredging operation has less, or at least no greater effect on sediment mobilization and mobility than a rain storm.”

All of these research studies have concluded that only a local significant effect occurs, with it decreasing rapidly downstream. The studies have been wide spread, having been undertaken in Alaska, Idaho, California, Montana and Oregon.

The science supports de minimus status for < 6-inch suction dredges. Turbidity is de minimus according to the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.

“Effects from elevated levels of turbidity and suspended sediment normally associated with suction dredging as regulated in the past in California appear to be less than significant with regard to impacts to fish and other river resources because of the level of turbidity created and the short distance downstream of a suction dredge where turbidity levels return to normal” (CDFG, 1997).

Furthermore, individuals that have not, in fact, operated suction dredges may not realize that it is a self-limiting operation. The dredge operator must be able to see his work area to operate safely and manage the intake of the dredge nozzle. If high levels of turbidity were to flood the dredger’s work area and render him “blind” he would have to move the operation to another location.

INCREASING WATER TEMPERATURE

Responsible suction dredge miners do not dredge stream banks (it is illegal). Dredging occurs only in the wetted perimeter of the stream. Therefore, it is unlikely suction dredging will cause a loss of cover adjacent to the stream.

Solar radiation is the single most important energy source for the heating of streams during daytime conditions. The loss or removal of riparian vegetation can increase solar radiation input to a stream increasing stream temperature. Suction dredge operations are confined to the existing stream channel and do not affect riparian vegetation or stream shade (SNF, 2001).

Suction dredging could alter pool dimensions through excavation, deposition of tailings, or by triggering adjustments in channel morphology. Excavating pools could substantially increase their depth and increase cool groundwater inflow. This could reduce pool temperature. If pools were excavated to a depth greater than three feet, salmonid pool habitat could be improved. In addition, if excavated pools reduce pool temperatures, they could provide important coldwater habitats for salmonids living in streams with elevated temperatures (SNF, 2001).

Dredge mining had little, if any, impact on water temperature (Hassler, T.J., W.L. Somer and G.R. Stern, 1986). In addition, the Oregon Siskiyou Dredge Study states, “There is no evidence that suction dredging affects stream temperature” (SNF, 2001).

Increases in sediment loading to a stream can result in the stream aggrading causing the width of the stream to increase. This width increase can increase the surface area of the water resulting in higher solar radiation absorption and increased stream temperatures. Suction dredge operations are again confined to the existing stream channel and do not affect stream width (SNF, 2001).

Stream temperature can also increase from increasing the stream’s width to depth ratio. The suction dredge operation creates piles in the stream channel as the miner digs down into the streambed. The stream flow may split and flow around the pile decreasing or increasing the wetted surface for a few feet. However, within the stream reach that the miner is working in, the change is so minor that the overall wetted surface area can be assumed to be the same so the total solar radiation absorption remains unchanged. Suction Dredging results in no measurable increase in stream temperature (SNF, 2001).

“Small streams with low flows may be significantly affected by suction dredging, particularly when dredged by larger dredges (Larger than 6 inches) (Stern, 1988). However, the California Department of Fish and Game concluded, “current regulations restrict the maximum nozzle size to 6 inches on most rivers and streams which, in conjunction with riparian habitat protective measures, results in a less than significant impact to channel morphology” (CDFG, 1997).

WATER CHEMISTRY

Concern has been raised that small-scale dredge operations may increase the metal load of the surface waters. Whereas dredge operations do re-suspend the bottom sediment, the magnitude of this disturbance on stream metal loading was unknown. It was unknown what affect the dredge operations may have on the transport and redistribution of metals-some of which (for example, arsenic, copper, and zinc) have environmental importance.

The U.S. Geological Survey and the Alaska Department of Natural Resources cooperated in a project, on Fortymile River, to provide scientific data to address these questions. This river is designated a Wild and Scenic Corridor by the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act. Current users of the river include placer mine operators, as well as boaters and rafters. Along the North Fork Fortymile River, and just below its confluence with the South Fork, mining is limited to a few small suction dredges which, combined, produce as much as a few hundred ounces of gold per year. In this area, some potential environmental concerns have been raised associated with the mining activities, including increased turbidity of the river water; adverse impact on the overall chemical quality of the river water; and potential additions of specific toxic elements, such as arsenic, to the river during mining operations.

Field measurements were made for pH, turbidity, electrical conductivity (a measure of the total dissolved concentrations of mineral salts), and stream discharge for the Fortymile River and many of its tributaries. Samples were collected at the same time for chemical analyses, including trace-metal analyses

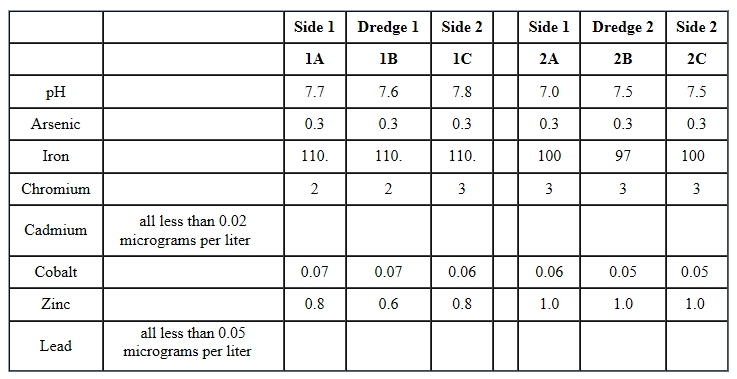

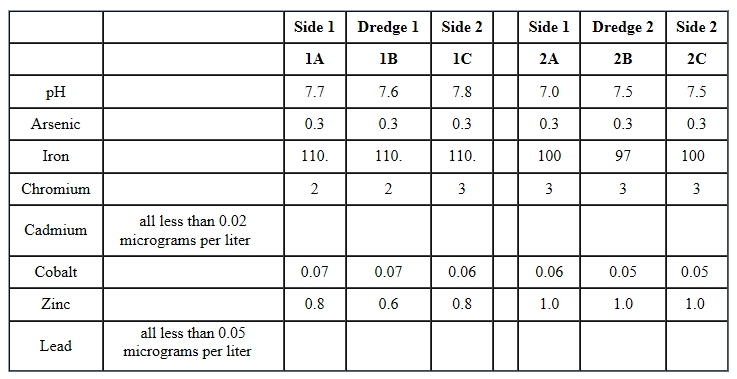

Water-quality samples were collected at three points 200 feet behind each of the two operating suction dredges. One sample was collected on either side of the plume, and one in the center of the plume. The samples were passed through a filter with a nominal pore size of 0.45 micrometers and acidified to a pH less than about 2. Results are shown in the following table. Samples 1A, 1C, 2A, and 2C are from either side of the plume behind dredges 1 and 2, respectively. Samples 1B and 2B are from the center of each plume. All concentrations given are in micrograms per liter, except pH, which is expressed in standard units.

The data show similar water-quality values for samples collected within and on either side of the dredge plumes. Further, the values shown in the table are roughly equal to or lower than the regional average concentrations for each dissolved metal, based on the analyses of 25 samples collected throughout the area. Therefore, suction dredging appears to have no measurable effect on the chemistry of the Fortymile River within this study area. We have observed greater variations in the natural stream chemistry in the region than in the dredge areas (Wanty, R.B., B. Wang, and J. Vohden. 1997).

A final report from an EPA contract for analysis of the effects on mining in the Fortymile River, Alaska stated, “This report describes the results of our research during 1997 and 1998 into the effects of commercial suction dredging on the water quality, habitat, and biota of the Fortymile River…. The focus of our work on the Fortymile in 1997 was on an 8-inch suction dredge (Site 1), located on the mainstem… At Site 1, dredge operation had no discernable effect on alkalinity, hardness, or specific conductance of water in the Fortymile. Of the factors we measured, the primary effects of suction dredging on water chemistry of the Fortymile River were increased turbidity, total filterable solids, and copper and zinc concentrations downstream of the dredge. These variables returned to upstream levels within 80-160 m downstream of the dredge. The results from this sampling revealed a relatively intense, but localized, decline in water clarity during the time the dredge was operating” (Prussian, A.M., T.V. Royer and G.W. Minshall, 1999).

“The data collected for this study help establish regional background geochemical values for the waters in the Fortymile River system. As seen in the chemical and turbidity data any variations in water quality due to the suction dredging activity fall within the natural variations in water quality” (Prussian, A.M., T.V. Royer and G.W. Minshall, 1999).

REMOVAL OF MERCURY FROM THE ENVIRONMENT

Looking for gold in California streams and rivers is a recreational activity for thousands of state residents. As these miners remove sediments, sands, and gravel from streams and former mine sites to separate out the gold, they are also removing mercury. This mercury is the remnant of millions of pounds of pure mercury that was added to sluice boxes used by historic mining operations between 1850 and 1890. Modern day small-scale gold suction dredgers do not use mercury to recover gold during the operation of the dredge. Therefore, any gold that would be found in their possession would be that which was extracted from the stream or river they are working.

Taking mercury out of streams benefits the environment. Efforts to collect mercury from recreational gold miners in the past, however, have been stymied due to perceived regulatory barriers. Disposal of mercury is normally subject to all regulations applicable to hazardous waste.

In 2000, EPA and California’s Division of Toxic Substance Control worked in concert with other State and local agencies to find the regulatory flexibility needed to collect mercury in a simple and effective manner. In August and September, 2000 the first mercury “milk runs” collected 230 pounds of mercury. A Nevada County household waste collection event held in September 2000 collected about 10 pounds of mercury. The total amount of mercury collected was equivalent to the mercury load in 47 years worth of wastewater discharge from the city of Sacramento’s sewage treatment plant or the mercury in a million mercury thermometers. This successful pilot program demonstrates how recreational gold miners and government agencies can work together to protect the environment (US EPA, 2001).

Mercury occurs in several different geochemical forms, including elemental mercury, ionic (or oxidized) mercury, and a suite of organic forms, the most important of which is methylmercury. Methylmercury is the form most readily incorporated into biological tissues and is most toxic to humans. The process of mercury removal by suction dredging does not contaminate the environment because small-scale suction dredging removes elemental mercury. Removal of elemental mercury before it can be converted, by bacteria, to methylmercury is a very important component of environmental and human health protection provided as a secondary benefit of suction dredging.

THE REAL ISSUE

The issue of localized conflict with suction dredgers and other outdoor recreational activities can be put into a more reasonable perspective using the data provided at the beginning of this report. For example, the total acreage of all analyzed claims related to the total acres of watershed is about 0.2 percent. The percentage of land area within riparian zones on the Siskiyou National Forest occupied by mining claims is estimated to be only 0.1 percent.” The report goes on to say, “Over the past 10 years, approximately 200 suction dredge operators per season operate on the Siskiyou National Forest (SNF, 2001).

The issue against suction dredge operations in the streams of the United States appears to be less an issue of environmental protection and more of an issue of certain organized individuals and groups being unwilling to share the outdoors with others without like interests.

Management of the Fortymile River region (a beautiful, wild and scenic river in the remote part of east-central Alaska) and its resources is complex due to the many diverse land-use options. Small-scale, family-owned gold mining has been active on the Fortymile since the “gold rush” days of the late 1880’s. However, in 1980, the Fortymile River and many of its tributaries received Wild and Scenic River status. Because of this status, mining along the river must compete with recreational usage such as rafting, canoeing, and fishing.

A press release from the U. S. Geological Survey stated, in part, the following, “The water quality of the Fortymile River-a beautiful, …has not been adversely impacted by gold placer mining operations according to an integrated study underway by the U.S. Geological Survey and the Alaska Department of Natural Resources.

Violation of mining discharge regulations would close down the small-scale mining operations. No data existed before this study to establish if the mining was degrading the water quality. However, even with the absence of data, environmental groups were active to close down mining on the river citing unsubstantiated possible discharge violations.

This study has found no violations to date to substantiate closure of the small-scale mining operations. The result is a continuance of a way of life on the last American frontier.” (U.S. Geological Survey October 27, 1998). I have no doubt that this is the real issue currently facing small-scale gold suction dredgers in California.

Suction dredges do not add pollution to the aquatic environment. They merely re -suspend and re-locate the bottom materials (overburden) within the river or stream.

I hope this scientific research information I have provided will be helpful in your efforts regarding suction dredge mining and water quality. I thank you for this opportunity to submit this data.

LITERATURE CITED

CDFG, 1997. draft Environmental Impact Report: Adoption of Amended Regulations for Suction Dredge Mining. State of California, The Resource Agency, Department of Fish and Game

Cooley, M.F. 1995. Forest Service yardage Estimate. U.S. Department of Agriculture, U.S. Forest Service, Siskiyou National Forest, Grants Pass, Oregon.

Griffith, J.S. and D.A. Andrews. 1981. Effects of a small suction dredge on fishes and aquatic invertebrates in Idaho streams. North American Journal of Fisheries Management 1:21- 28.

Harvey, B.C., K. McCleneghan, J.D. Linn, and C.L. Langley, 1982. Some physical and biological effects of suction dredge mining. Lab Report No. 82-3. California Department of Fish and Game. Sacramento, CA.

Harvey, B.C. 1986. Effects of suction gold dredging on fish and invertebrates in two California streams. North American Journal of Fisheries Management 6:401-409.

Hassler, T.J., W.L. Somer and G.R. Stern. 1986. Impacts of suction dredge mining on anadromous fish, invertebrates and habitat in Canyon Creek, California. California Cooperative Research Unit, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Humbolt State University. Cooperative Agreement No 14-16-0009-1547.

Huber and Blanchet, 1992. Water quality cumulative effects of placer mining on the Chugach National Forest, Kenai Peninsula, 1988-1990. Chugach National Forest, U.S. Forest Service, Alaska Region, U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Lewis, 1962. Results of Gold Suction Dredge Investigation. Memorandum of September 17, 1962. California Department of Fish and Game, Sacramento, CA. North, P.A., 1993. A review of the regulations and literature regarding the environmental impacts of suction gold dredging. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Region 10, Alaska Operations Office. EP 1.2: G 55/993.

Prussian, A.M., T.V. Royer and G.W. Minshall, 1999. Impact of suction dredging on water quality, benthic habitat, and biota in the Fortymile River, Resurrection Creek, and Chatanika River, Alaska, FINAL REPORT. US Environmental Protection Agency, Region 10, Seattle, Washington.

SNF, 2001. Siskiyou National Forest, Draft Environmental Impact Statement: Suction Dredging Activities. U.S. Department of Agriculture, U.S. Forest Service, Siskiyou National Forest, Medford, OR.

Somer, W.L. and T.J. Hassler. 1992. Effects of suction-dredge gold mining on benthic invertebrates in a northern California stream. North American Journal of Fisheries Management 12:244-252

Stern, 1988. Effects of suction dredge mining on anadromous salmonid habitat in Canyon Creek, Trinity County, California. M.S. Thesis, Humbolt State University, Arcata, CA.

Thomas, V.G. 1985. Experimentally determined impacts of a small, suction gold dredge on a Montana stream. North American Journal of Fisheries Management 5:480-488.

US EPA, 2001. Mercury Recovery from Recreational Gold Miners. http://www.epa.gov/region09/cross_pr/innovations/merrec.html

Wanty, R.B., B. Wang, and J. Vohden. 1997. Studies of suction dredge gold-placer mining operations along the Fortymile River, eastern Alaska. U.S. Geological Survey Fact Sheet FS-154-97.