By Dave McCracken

Finding wild adventure, wonderful new friends, and riches in gold inside one of the most remote locations on the planet!

This story is dedicated to my long-time, trusted friend, Mark Chestnut. He and I teamed up to perform a preliminary assessment of the gold dredging potential in the deepest remote jungles of Borneo, Indonesia. The ultimate success of this mission was largely the result of Mark’s professionalism and dedication to getting the work done under some very difficult conditions.

This story is dedicated to my long-time, trusted friend, Mark Chestnut. He and I teamed up to perform a preliminary assessment of the gold dredging potential in the deepest remote jungles of Borneo, Indonesia. The ultimate success of this mission was largely the result of Mark’s professionalism and dedication to getting the work done under some very difficult conditions.

On his own, Mark led sampling expeditions with his team of Dyak helpers for days at a time into places where I am entirely certain that no outsider has ever been before, living under fly camps with the natives, eating the food they prepared from the jungle, running down through narrow gorges in long boats where the ride was so violent, that all of the boat paddles were broken along the way. I am very careful who I take along with me on these projects. Those that go must be of the highest caliber. Not only would I take Mark with me anywhere, but I would be comfortable in sending him to manage a project. There are only a few people I have worked with in our industry that I would trust with that responsibility.

Indonesia’s 13,677 islands stretch across 3,000 miles of ocean. Only around 6,000 of these islands have been named, and only 900 of those have been permanently settled. The principal islands of Indonesia are Java, Sumatra, Sulawesi, and Kalimantan (Indonesian Borneo).

Indonesia’s 13,677 islands stretch across 3,000 miles of ocean. Only around 6,000 of these islands have been named, and only 900 of those have been permanently settled. The principal islands of Indonesia are Java, Sumatra, Sulawesi, and Kalimantan (Indonesian Borneo).

Three-quarters of the island of Borneo is called Kalimantan, and is part of Indonesia. The northeastern part of the island is owned by Malaysia.

Throughout history, Borneo, which is the world’s third largest island, has been a mythical location of indescribable riches and unfathomable mystery. Early explorers and traders sailed the pirate-infested waters of Indonesia and Borneo for many centuries, trading for prized jungle products, diamonds and gold, but generally staying clear of the forbidden unknown interior, which was known to be prowled by savage headhunters and cannibals.

The natives of Borneo, known as Dyaks, believed that the power of any individual was contained in his head. To cut the head off, and to possess it, was therefore to possess that individual’s power. The power of a head diminished over time, making it necessary to obtain new, additional heads; the more heads, the more power. While most often, Dyak tribes battled against each other, any outsider was also fair game.

Usually, head-hunting raids were well-organized ventures led by a supreme commander, in which hundreds of men would participate. The main weapon was a mandau (machete), which was made by Dyak blacksmiths, working with native ores and primitive forges. Early explorers reported these machetes held an edge capable of slicing a musket barrel in half! Shields were made of ironwood, following the longitudinal grain, so an enemy’s mandau would become wedged deeply enough to become lodged and pulled out of his grasp.

After a war party was fully organized, a Dyak medicine man would perform a ceremony to weigh and balance the different omens. If all was in order, the war party would usually travel by native long boat to a distance which was several hours on foot from the enemy village. Sometimes, the enemy would be pre-warned by their own hunting parties; and they themselves would mount an ambush on the raiding war party. In this case, the ambush was usually begun by firing poison darts onto the unsuspecting enemy with blowguns, and then hand-to-hand combat with spears and mandaus.

Captured women and children from a village were forced into slavery, and the village was looted of its valuables, especially traded goods from China and India. A celebration always followed a successful head-hunting raid. Those who brought back heads were heroes.

Head-hunting was practiced widely throughout the interior of Borneo up until the Second World War. Now, it is a thing of the past.

Because of the impassable mountains and rivers, much of the interior of Borneo is not accessible by automobile. Access to a portion of the interior can be accomplished by riverboat, but waterfalls and severe rapids prevent deeper penetration. Access to the most remote locations generally is accomplished by the use of helicopters. There are some landing strips in the interior. Small planes can be chartered, but quickly changing weather conditions can make even this type of access unpredictable.

Because of the impassable mountains and rivers, much of the interior of Borneo is not accessible by automobile. Access to a portion of the interior can be accomplished by riverboat, but waterfalls and severe rapids prevent deeper penetration. Access to the most remote locations generally is accomplished by the use of helicopters. There are some landing strips in the interior. Small planes can be chartered, but quickly changing weather conditions can make even this type of access unpredictable.

Our mining venture was into one of the most remote and least-explored sections of Borneo’s interior. Going in by helicopter, we crossed over hundreds of miles of impenetrable jungle. There were mountains, having sheer cliffs hundreds of feet in height, extending for miles. We crossed over hundreds of rivers, many which were raging white-water. I remember hoping, as I always do when traveling by helicopter, that we would not crash. Because if I managed to survive the crash, I was gauging the magnitude of the effort it would take to return to civilization. It would be next to impossible!

The reason we were in Borneo was to perform a preliminary evaluation to gauge the potential success of a production gold dredging operation. Some base camps had been already built in the area by the company that hired us; some dredges were already on site; and the local natives were using the dredges when we arrived. We spent 30 days in the jungle, living and working with the native miners, learning their way of life and survival in the jungle.

The reason we were in Borneo was to perform a preliminary evaluation to gauge the potential success of a production gold dredging operation. Some base camps had been already built in the area by the company that hired us; some dredges were already on site; and the local natives were using the dredges when we arrived. We spent 30 days in the jungle, living and working with the native miners, learning their way of life and survival in the jungle.

The natives involved on our project were from two different villages. They were all very friendly and helpful. All were in excellent physical condition and used to hard physical work. Most were already familiar with basic gold mining techniques, since they have been mining gold by primitive methods for many generations.

Generally, no matter what else they wear for clothes, the natives wear nothing on their feet. Often, all the men wear is a pair of underpants. On one occasion, I went on a nine-hour prospecting/hunting expedition, where the terrain was so slippery and steep, most of the climbing was done with our arms. We scaled sheer cliffs with narrow, slippery walkways, where the bedrock was so sharp it cut into the soles of my jungle boots. The clay-like ground was so slippery, it was like walking on ice during most of the hike. I like to think that I personally am in pretty good shape. The pace was very fast, but was only a third of their normal speed. They had to slow down to allow us to keep up. I almost wore out a good set of authentic military jungle boots, and I had blisters on my own feet long before the expedition was finished. The natives were all barefooted, and not one had a cut or a bruise at the end of the day!

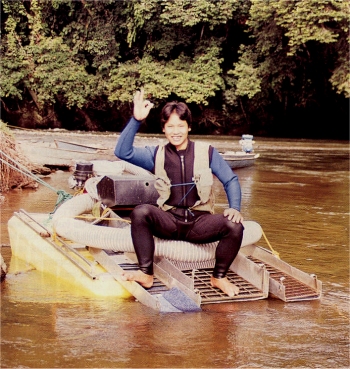

You have to be careful where you stick your hands at the bottom of tropical rivers!

You have to be careful where you stick your hands at the bottom of tropical rivers!

The native men in the jungles of Borneo have a simple, adventuresome life–the kind that every little boy dreams of in America. Their responsibilities consist of hunting, fishing, finding gold and raising their families. For lack of any exterior form of entertainment, the family unit is very close there. These people create their own entertainment, excitement and adventure.

We found that while they were all very strong and helpful, they were also always fun to be around. Operating gold dredges was a new adventure for most of them, and they were having a good time learning how to do it.

The natives also have a high level of self-preservation, probably because their lifestyle is so closely connected to the basics of survival. On one occasion, after we had shut down a production dredge, one of the divers was bumped off the dredge into fast, deep water wearing a full vest of weights and no air. He was connected to a 100-foot airline. The airline was wrapped around something under the dredge, so no one could get at it. We all stood there and watched while this native pulled himself 100 feet up-stream, underwater, against a strong current without ever coming to the surface. We felt him frantically tugging one pull at a time. It never occurred to anyone that he might drown. When he reached the dredge, the look of agony disappeared into an uproar of laughter as he took his first breath. After that, we all used the same signal of frantically thrashing for air every time we wanted to communicate the danger in dredging a particularly difficult location. We always laughed when using the signal.

On one expedition, it was necessary for our guides to cut down a large hardwood tree to replace most of the paddles we needed to continue our journey.

On one expedition, it was necessary for our guides to cut down a large hardwood tree to replace most of the paddles we needed to continue our journey.

The natives are also very adept with the use of a chainsaw. They are able to cut down a tree and slice straight boards out, without the use of any guides whatsoever. Compared to other jungle expeditions I have been on, we lived in luxurious base camps, with showers, sleeping quarters, meeting areas, dining areas–all on stilts ten feet off the ground. The base camps were clean, dry and comfortable–put together from lumber sliced out of trees solely from the use of a chainsaw. The long boats we were using also were made from the same lumber.

Because of the steep, rough terrain in the Borneo jungle, almost all travel is done by boat on the intricate river system. Consequently, all of the native men are skilled in the handling of their keting tings (native long boats). These boats are usually around 30 feet long and about 3 1/2 feet wide. These days, they are powered by 4-stroke engines, 8 and 10 horsepower Yamahas were being used in our area of operation. A long shaft mechanism is connected to the engine with a propeller on the end. The boat operator is able to manipulate the long shaft and propeller around like a rudder, but is also able to control how deep the propeller extends into the water. In this way, the keting tings can be maneuvered through

We went down through rapids which, as we approached, I thought the natives were just playing a trick, with a plan to turn around at the very last minute. Rapids with waves nearly 4 feet higher than the gunwales of the boat on both sides. And then, afterwards, we would come right back up through these rapids. At first, I thought this was reckless and chancy. Later, I realized it was routine. In thirty days, we never saw a single boat get into trouble.water only inches deep, even when transporting 1500 pounds or more of personnel, equipment or supplies.

It did not take long for me to realize the long shaft mechanism is the most effective means developed to propel long boats on shallow rivers. These long shaft propulsion systems are used all throughout Asia.

It did not take long for me to realize the long shaft mechanism is the most effective means developed to propel long boats on shallow rivers. These long shaft propulsion systems are used all throughout Asia.

On one particular prospecting trip into the headwaters of a river, we rode these boats down through whitewater canyons so narrow that the sides and bottoms of the long boats were scraping the sides of the canyon on both sides–and we were going faster than a roller-coaster ride. What was most amazing to us, was that somehow, the natives were able to get the long boats up through those canyons! We were personally dropped in at the top by helicopter.

The operation supplied us with bottled water to drink, rice to eat, and the other basics which we needed. The natives had gardens and supplied us with fresh vegetables. There was a hunting team which supplied us with fresh wild boar and deer meat on a daily basis, and fresh fish from the river. Native cooks prepared the food for us, and we could not have found better food in most of the restaurants in Indonesia or elsewhere.

Notice the slash across the pig’s head?

Hunters use dogs to track down wild game–usually the babi hutan (wild boars). Often, a hunter will go out alone with a single dog. The dog catches the scent of a boar and starts barking. When the dog catches up with the boar, the boar will turn on the dog and stand there to defend itself. Meanwhile, the native hunter catches up and will either attack the boar with his spear; or more often, the boar will attack the hunter. When the boar attacks, the hunter sidesteps at the last second, and slashes the backside of the boar’s head with his mandau in a single downward stroke. This is kind of a ritual, like bull fighting in Mexico. The hunters take pride in returning with wild boars having the familiar slash on the back of the head. Most boars that were brought in were killed in this manner. Some hunters brought in two and three boars on a single day to feed the whole crew.

They also brought in payau (deer)–sometimes killed with a spear, and sometimes brought in alive. The natives and their dogs have a method of running down a deer alive, so it can be preserved until the meat is needed.

The natives also hunt bears; but this is usually accomplished also with the use of their blow guns. They weaken the bear with poison darts and go in for the final kill with a spear.

My earlier experiences in remote jungles always involved animal life which was dangerous to us while dredging in the river. I expected no less in Borneo. However, while we did see some very large buaya (alligators), the natives assured us that they have never been known to attack a man. Apparently, they like their meat dead and rotten.

My earlier experiences in remote jungles always involved animal life which was dangerous to us while dredging in the river. I expected no less in Borneo. However, while we did see some very large buaya (alligators), the natives assured us that they have never been known to attack a man. Apparently, they like their meat dead and rotten.

The main river was actually pretty large in size!

During our prospecting, the natives did show us one specific area where the water runs muddy all the time–even when the water is running clear just upriver. The natives explained that the muddy water was either being stirred up by dragons or alligators. Needless to say, we did not bother to sample in that location.

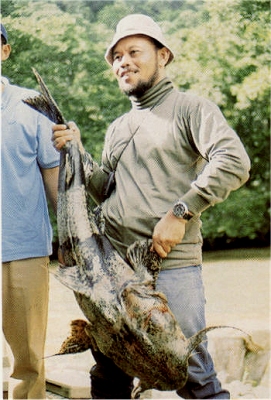

The natives did tell us to be careful of the kujut (huge catfish) at the bottom of the rivers. While we did not see any underwater, native fishermen did catch one catfish which weighed around 60 pounds. It was large enough, and had big enough teeth, to take a man’s hand away. The natives said this was a small fish! Apparently, on the larger rivers, the natives have trouble with losing their dogs to these catfish. Some villages use full-grown live ducks as bait to catch these big catfish. They told us there has never been an occasion where a full-grown man has been attacked and eaten by a catfish. This, however, didn’t make us feel all that much safer while underwater.

We set up fly camps alongside the river when we prospected distant areas from the base camp.

Actually, as far as wildlife goes, it was the pacer (ground leeches) that had most of our attention. Luckily, there were no leeches in the river! But, if you needed to go up on the river banks, or if you were going to take any kind of hike through the jungle, you were going to get leeches on you. They were everywhere! Some bushes had blood-sucking leeches on every leaf–on every branch!

Actually, as far as wildlife goes, it was the pacer (ground leeches) that had most of our attention. Luckily, there were no leeches in the river! But, if you needed to go up on the river banks, or if you were going to take any kind of hike through the jungle, you were going to get leeches on you. They were everywhere! Some bushes had blood-sucking leeches on every leaf–on every branch!

The biggest problem with leeches is psychological. They are slimy, sleazy creatures. You just naturally want to get them off you as quickly as possible. When you try and brush a leech off with your hand, it then sticks to your hand like glue. When you use your other hand to get it off, it ends up on that hand. Meanwhile, there are two or three more sleazing up your legs–or maybe a dozen, depending upon where you are standing or walking. Leeches move pretty fast!

Leeches have a very strong sucker-mouth, which attaches to your skin and sucks the blood right out. It doesn’t take long. In fact, they can attach to the outside of a thin pair of pants, or on the outside of a T-shirt, or on the outside of a cotton sock, and suck the blood right through the garment. It is all pretty slimy business! The nice thing about these leeches is that they do not carry any disease.

When we started, I figured we had it together over the natives with our lightweight long-sleeve shirts, tucked into our thick Levis, which were tucked into our jungle boots. All most of the natives were wearing on the hikes was a pair of shorts or underpants! However, it soon became obvious that the natives could easily find and remove the leeches from their own bodies. Sometimes, we didn’t find a few of our leeches until we got back to camp. Generally, a leech will drop off you once it has had its fill of blood.

“Leeches do not hurt you. What’s a little blood? We found the best way to get them off was by scraping them off with the sharp blade of a knife.”

A small red mark on your skin is left where a leach has been sucking. It goes away after a few weeks. The natives told us leeches are used regularly to suck the infection from injuries in their native medicine.

Overall, the adverse animal conditions were very mild–compared to the crocodiles, piranha, electric eels, African Killer Bees, black flies, mosquitoes, and poisonous vipers we have encountered in similar jungle conditions in the Amazon and elsewhere. I was only bitten by one mosquito in 30 days! A few leeches are not a bad trade-off for not having to deal with truly dangerous critters.

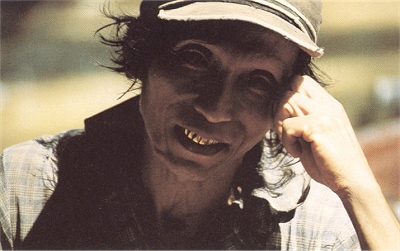

Our guides and helpers were a good bunch of guys to have on the team.

Our guides and helpers were a good bunch of guys to have on the team.

We did have several very amusing experiences having to do with leeches. Where is the worst place a man can get a leech stuck onto him? One day, we were riding upriver in a keting ting. These long boats usually have one person operating the motor, and another person in the bow with a paddle to help keep the boat pointed in the right direction, and to signal the boat driver to watch out for submerged rocks and logs. We had just finished a short prospecting hike, and thought we had removed all the leeches from our bodies. It always seems, however, that no matter how thorough you are, a few more show up afterwards. We were going upstream through a boulder-ridden section of river, when the bow man jumped up and yanked his shorts down. Right there, in the worst place imaginable, was a leech hanging off the man. One of the other natives pulled out his machete to give him some help. Just at that time, the boat rammed into a submerged log, and the bow man flew overboard. We all just had to stop and laugh for the longest time before we could get going again. Needless to say, this was a subject we all laughed about right up until the time of our departure.

During our sampling operation, we spent a great deal of time traveling many, many miles around in the long boats. It was a great way to get a good look at the jungle and the wildlife. In many places, the trees grow out across the river from both sides to make a natural tunnel.

During our sampling operation, we spent a great deal of time traveling many, many miles around in the long boats. It was a great way to get a good look at the jungle and the wildlife. In many places, the trees grow out across the river from both sides to make a natural tunnel.

One day, we were traveling by boat along the river’s edge, when a large biawak (lizard several feet long, with sharp teeth and very fast) jumped off a tree limb directly into the boat in front of me. He would have landed on top of the native in front of me, but the native, ever alert, saw it coming. I saw it out of the comer of my eye, but thought it was just a branch falling out of the tree. The native jumped up just in time, and the lizard fell into the bottom of the boat between his bare feet. Then, yelling like a mad man, the native and lizard both danced around quickly, trying to get out of each other’s way. Finally, the lizard went over the side. All this, about three feet in front of me; and so fast, I didn’t have a chance to react! We all laughed so hard that we almost had to pull the boat over to the edge of the river.

One day, while prospecting, we came around a bend in the river, traveling by keting ting, and a million fruit bats took to the air. Known also as “flying foxes”, these are huge bats with wingspans of two to three feet. There were so many that it was like a dark cloud above us as we traveled beneath them on our way downriver.

Mark Chestnut poses for a photo with his sampling team after returning from a 5-day sampling project deep into another world where no outsider has ever gone before or since.

Mark Chestnut poses for a photo with his sampling team after returning from a 5-day sampling project deep into another world where no outsider has ever gone before or since.

Some of the local natives also hunt a certain breed of monkey, not for the meat, but for a particular healing stone possessed by only one special monkey in each tribe. Apparently, these healing stones are in great demand by Chinese medicine men, and a very high price is paid for them, much more than the price of gold by weight.

According to the local natives, if a monkey becomes sick, the special monkey will pass the stone to the sick monkey until he or she is healed. The problem for the monkey hunters is in determining exactly which monkey is carrying the stone. A sumpit (blow gun) is used to fire a poisoned dart at the monkey. Blow guns are made of a single piece of ironwood at least two meters in length, with a straight hole bored through its center. The darts are made from bamboo, and are dipped in a deadly poison made from the sap of a Tajom tree mixed with the venom from a cobra.

We ran into a few monkey hunters during one of our expeditions. These men hunt for gold during the dry periods when the water is low in the rivers. They hunt for monkey stones during the rainy periods. We noticed immediately that the monkey hunters each had almost a full mouth of solid gold teeth. When I inquired about this, the natives told us the poison used on blow gun darts is so toxic, that just the vapors near the mouthpiece of a loaded blowgun will cause a person’s teeth to fall out after a period of time. Besides, solid gold teeth are fashionable in Borneo, similar to clean, white teeth in our culture.

our culture.

I noticed that many of the natives had gold teeth. I never did find out exactly how gold teeth are fashioned and how dentistry is performed deep inside the Borneo jungle. Many of the older men and women have tattoos on their hands, legs and arms. We were told the tattoos are made with tiny metal needles dipped in a particular tree sap, or in charcoal, leaving permanent black marks.

The predominant religion in the area of our operation was Christianity. The natives preferred to take Sunday off to conduct their own religious services. This was added to by other, more ancient rituals and customs. For example, after we had arrived and began our dredging activities, the rains started picking up. One of the natives had a dream that the local jungle guardian spirits were angry because of the loud noise of the engines brought in by the foreigners (us). Many of the natives worried over this dream, considering it might be a bad omen. Word reached the main village many hours up river. Within a few days, a whole delegation came down to our base camp led by the village chief.

The following day, they put on a ceremony along the edge of the river, while sacrificing the heads of two chickens to appease the jungle spirits. All of the local natives showed up to participate. All work was cancelled for the day. The following day, the weather cleared up, and operation conditions were improved until the time of our departure. Coincidence? The local natives didn’t believe so. Me? I choose to go along with the local customs of the natives of any area which is providing the hospitality. Who am I to challenge the beliefs of others? The natives believe Borneo is an old land, and that old spirits still linger around to help control the weather and certain events to protect the animals and local people. We found that different villages had this same belief, but had their own rituals for making peace with the spirits.

We had fried chicken for dinner on the night of the ritual. Uhm uhm good!

The local miners are recovering gold from the rivers by panning with their Tulangs (gold pans). These are similar to the Sarukas used in South America. They also use their keting ting motors to wash the streambed material from bedrock, so the flakes and nuggets can be exposed and removed from the bedrock cracks and traps. Some of the natives were using hoes underwater to rake gravel off the bedrock. They would then dive down using a facemask to recover gold from the bedrock traps. Sometimes they hit hot spots and do quite well.

One native told us he recovered over four kilograms (around ten pounds) of gold, mostly nuggets, in several months of hard work by primitive methods. But they don’t really need to recover a lot of gold. The jungle provides for most of their needs. Their villages also produce woven baskets and other products from the jungle which are exported to the outside world. A little gold allows for extra luxury items which improve their standard of living.

Local miners are doing very well by blowing gravel off the bedrock using their long-shaft propulsion systems!

I think the thing that impressed me most during the entire expedition was the friendliness of the people. Children ran out and waved at us when we went past their villages by long boat. Adults invited us to stay with them in their homes. The Chief of one village gave me his own favorite blowgun, one which he had personally used for the past 12 years.

Dyak sampling team

Dyak sampling team

The natives were excited to dredge with us, because it was explained to them that we were “professionals, gold prospectors from the outside world.” They pretty-much had taught themselves to dredge from scratch during the two months prior to our arrival. Except for when the water was muddy, they would insist on going down to help us. They wanted to participate also in the muddy water, but we insisted that it was too dangerous, because someone might get hit in the head with a rock.

Just like during any other activity, these natives dredge barefooted. Even the individuals who were wearing wetsuits wore nothing on their feet!

Instead of lead weight belts, they were wearing jacket-like vests, tied together with fishing line, with big pockets. River rocks were stuffed into the pockets to weigh down the diver. It seemed to work alright for them, but I’ll stick to my lead weight belt and steel-tipped rubber boots! Of course, we had to be very careful to avoid throwing rocks on unprotected toes.

Instead of lead weight belts, they were wearing jacket-like vests, tied together with fishing line, with big pockets. River rocks were stuffed into the pockets to weigh down the diver. It seemed to work alright for them, but I’ll stick to my lead weight belt and steel-tipped rubber boots! Of course, we had to be very careful to avoid throwing rocks on unprotected toes.

And we found gold; lots of it. We intend to return to Borneo with a larger sampling team and do a much more involved sampling program. If this project goes well, the company is interested in our bringing over an even larger team of experienced dredgers to work on a gold- sharing venture.

There is a lot of gold in East Kalimantan (Borneo). In the deep jungle, because of a rather steep gradient, the gravel inside most rivers I observed was generally very shallow to bedrock. Just like in California, some rivers had lots of fine gold, and some had jewelry gold–two ounce-sized nuggets, and much larger, are not uncommon. In the areas we sampled, the smaller-sized tributaries all seemed to carry a steady line of nugget and jewelry-sized gold, usually under a foot or two of hard-packed streambed material. Huge sections of exposed rough and cracked bedrock are common all along the rivers and creeks, which have never been prospected with a metal detector. We found gold lying all over some exposed rough bedrock in one area we were sampling. And we found deposits in the main river which could potentially yield pounds of gold or more per day to a production-dredging team. Because of the complete lack of modern suction dredging equipment during the past, many river channels are completely virgin of earlier mining activity and the opportunity is extraordinary.

There is a lot of gold in East Kalimantan (Borneo). In the deep jungle, because of a rather steep gradient, the gravel inside most rivers I observed was generally very shallow to bedrock. Just like in California, some rivers had lots of fine gold, and some had jewelry gold–two ounce-sized nuggets, and much larger, are not uncommon. In the areas we sampled, the smaller-sized tributaries all seemed to carry a steady line of nugget and jewelry-sized gold, usually under a foot or two of hard-packed streambed material. Huge sections of exposed rough and cracked bedrock are common all along the rivers and creeks, which have never been prospected with a metal detector. We found gold lying all over some exposed rough bedrock in one area we were sampling. And we found deposits in the main river which could potentially yield pounds of gold or more per day to a production-dredging team. Because of the complete lack of modern suction dredging equipment during the past, many river channels are completely virgin of earlier mining activity and the opportunity is extraordinary.

Because of the inaccessibility of the gold bearing areas, Borneo is probably not a good place for the casual, small-scale dredge operator. However, with the proper infrastructure set up (expensive), Borneo could be a modern gold dredger’s dream come true!

One of the consultants on this project told me he first went to East Kalimantan about nine years ago, He said he has known many people who have never been able to get it out of their system, He himself pretty-much has lived there ever since. He told me “once you drink from the waters of East Kalimantan, you will always need to return again.” There is something about the area, the natives, the lifestyle–measured against the fast-paced rat race of our own lifestyle that makes one wonder… Whether it is because of the adventure, the kindness of the natives, the gold nuggets and great mining opportunities, or the water—or maybe a little of each of these things, I know that I personally will be going back!

- Here is where you can buy a sample of natural gold.

- Here is where you can buy Gold Prospecting Equipment & Supplies.

- More About Gold Prospecting

- More Gold Mining Adventures

- Schedule of Events

- Best-selling Books & DVD’s on this Subject