By Dave McCracken

Any place along the gold path where there is protection from the main flow of water is a good location to sample for gold.

Thorndike/Barnhart’s Advanced Dictionary defines “placer” as “A deposit of sand, gravel or earth in the bed of a stream containing particles of gold or other valuable mineral.” The word “geology” in the same dictionary is defined as “The features of the earth’s crust in a place or region, rocks or rock formations of a particular area.” So in putting these two words together, we have “placer geology” as the nature and features of the formation of deposits of gold and other valuable minerals within a streambed

Thorndike/Barnhart’s Advanced Dictionary defines “placer” as “A deposit of sand, gravel or earth in the bed of a stream containing particles of gold or other valuable mineral.” The word “geology” in the same dictionary is defined as “The features of the earth’s crust in a place or region, rocks or rock formations of a particular area.” So in putting these two words together, we have “placer geology” as the nature and features of the formation of deposits of gold and other valuable minerals within a streambed

The main factor causing gold to become deposited in the locations where it does is its superior weight over the majority of other materials which end up in a streambed. By superior weight, I mean that a piece of gold will be heavier than most any other material which displaces an equal amount of space or volume. For example, a large boulder will weigh more than a half-ounce gold nugget; but if you chip off a piece of the boulder which displaces the exact same volume or mass as the gold nugget, the nugget will weigh about six times more than the chip of rock.

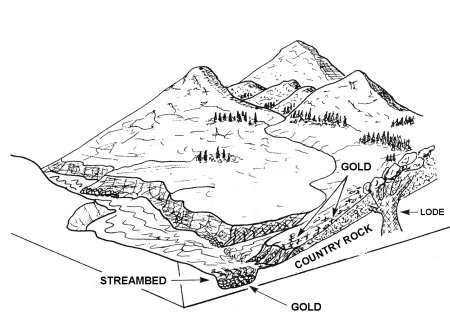

As gold is eroded from its original lode, gravity, wind, water and the other forces of nature may move it away and downwards until it eventually arrives in a streambed.

Gold erodes from its natural lode and eventually

is washed into an active waterway.

There are several different types of gold deposits that a prospector should know about, because they have different characteristics and are dealt with in different ways. They are as follows:

RESIDUAL DEPOSIT: A “residual deposit” consists of those pieces of the lode which have broken away from the outcropping of the vein due to chemical and physical weathering, but have not yet been moved or washed away from the near vicinity of the lode. A residual deposit usually lies directly at the site of its lode.

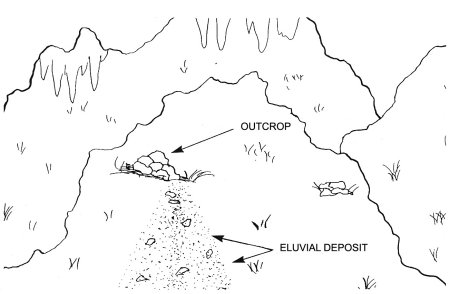

ELUVIAL DEPOSIT: An “eluvial deposit” is composed of those pieces of ore and free gold which have eroded from a lode and have been moved away by the forces of nature, but have not yet been washed into a streambed. The fragments of an eluvial deposit are often spread out thinly down along the mountainside below the original lode. Usually, the various forces of nature cause an eluvial deposit to spread out more as its segments are washed further away from the lode deposit. Individual pieces of an eluvial deposit are popularly known as “float.”

An eluvial deposit contains those pieces of ore that have been swept

away from the lode which have not yet been deposited by running water.

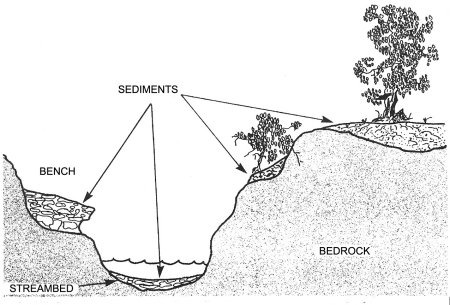

BENCH DEPOSIT: (Also “terrace deposit”) Once gold reaches a streambed, it will be deposited in common ways by the effects of running water. Most of the remainder of this article will cover these ways. During an extended period of time, a stream of water will to cut deeper into the earth. This leaves portions of the older sections of streambed high and dry. Old streambeds which now rest above the present streams of water are referred to as “benches.” Accumulations of gold and other valuable minerals contained in an old, high streambed are called “bench deposits.”

An eluvial deposit might be swept down to rest on top of an old streambed (bench), but it will still remain as an eluvial deposit until it is washed into a stream of water. A bench placer deposit contains the gold deposited within that streambed before it was left high and dry.

Many benches are lying close to the present streams of water, and are actually the remains of the present stream as it ran a very long time ago.

Some dry streambeds (benches) are situated far away from any present stream of water. These are sometimes the remains of ancient rivers which ran before the present river systems were formed. Ancient stream benches are sometimes on top of mountains, far out into the deserts, or can be found near some of today’s streams and rivers. Ancient streambeds, wherever found, can contain rich deposits of gold.

Most surface placer gold mining operations today direct their activities at bench deposits. The reason for this is that the presence of an old streambed is evidence that it has never been mined before. Any gold once deposited there will still be in place.

STREAM PLACER: In order to discuss what happens to gold when it enters a stream of water, it is first necessary to understand the two terms: “bedrock” and “sediments.” Many millions of years ago, when the outer perimeter of the earth cooled, it hardened into a solid rock surface–called “bedrock” (or “country rock” when discussing the subject of lodes). All of the loose dirt, rocks, sand, gravel and boulders which lie on top of the earth’s outer hardrock surface (bedrock) are called “sediments.” In some areas, the sedimentary material lays hundreds of feet deep. In other areas, especially in mountainous country and at the seashore, the earth’s outer crust (bedrock) is completely exposed. Bedrock can usually be observed by driving down any highway and looking at where cuts have been made through the hard rock in order to make the highway straight and level.

Streambeds are composed of rocks, sand, gravel, clay and boulders (sediments) and always form on top of the bedrock foundation (although they can be later covered up by volcanic activity). Bedrock and country rock are the same thing.

Streambeds are composed of sediments which lie on top of bedrock.

The following video segment will allow you a visual demonstration of these very important points:

A large storm in mountainous country will cause the streams and rivers within the area to run deeper and faster than they normally do. This additional volume of water increases the amount of force and turbulence that flows over the top of the streambeds lying at the bottom of these waterways. Sometimes, in a very large storm, the increased force of water is enough to sweep the entire streambed down the surface of its underlying bedrock foundation. It is this action which causes a streambed to cut deeper into the earth over an extended period of time. A storm of this magnitude can also erode a significant amount of new gold into the streambeds where it will mix with the other materials.

A large storm in mountainous country will cause the streams and rivers within the area to run deeper and faster than they normally do. This additional volume of water increases the amount of force and turbulence that flows over the top of the streambeds lying at the bottom of these waterways. Sometimes, in a very large storm, the increased force of water is enough to sweep the entire streambed down the surface of its underlying bedrock foundation. It is this action which causes a streambed to cut deeper into the earth over an extended period of time. A storm of this magnitude can also erode a significant amount of new gold into the streambeds where it will mix with the other materials.

Gold, being heavier than the other materials which are being swept downstream during a large storm, will work its way quickly to the bottom of these materials. The reason for this is that gold has a much higher specific gravity than the other streambed materials and so will exert a downward force against them. As the streambed is being vibrated and tossed around and pushed along by the tremendous torrent of water caused by the storm, gold will penetrate downward through the other materials until it reaches something which will stop its descent-like bedrock. This very important principle is demonstrated by the following video segment:

With the exception of the finer-sized pieces, it takes a lot of force to move gold. Since gold is about 6 times heavier than the average of other materials which commonly make up a streambed, it takes a lot more force to move gold down along the bedrock than it does to move the other streambed materials.

So there is the possibility of having enough force in a section of river because of a storm to sweep part of the streambed away, yet perhaps not enough force to move much of the gold lying on bedrock.

When there is enough force to move gold along the bottom of a riverbed, that gold can then become deposited in a new location wherever the force of the flow is lessened at the time of the storm.

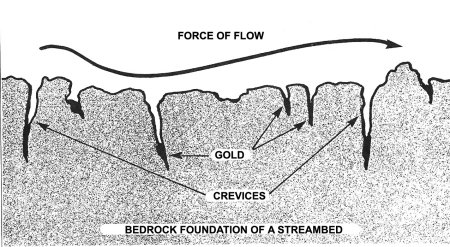

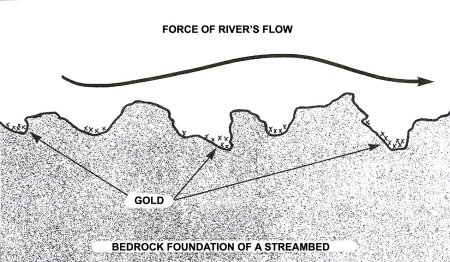

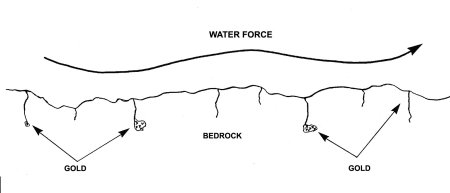

Bedrock irregularities at the bottom of a streambed play a large role in determining where gold will become trapped. A crack or crevice along the bedrock surface is one good example of a bedrock gold trap.

Streambeds are composed of sediments which lie on top of bedrock.

Many bedrock gold traps are situated so that the main force of water, being enough to move gold, will sweep the traps clean of lighter streambed materials. This leaves a hole for the gold to drop into and become shielded from the main force of water and material which is moving across the bedrock. And there the gold will remain until some fluke of turbulence boils it out of the hole and back into the main force of water again, where it can then become trapped in some other such hole, and so on. The following video segment further demonstrates these important points:

Some types of bedrock are very rough and irregular, which allows for many, many gold traps along its surface.

Some bedrock surfaces are very rough and

irregular–which allows for many gold traps.

How well a crevice will trap gold depends greatly upon the shape of the crevice itself and its direction in relation to the flow of water during a flood storm. Crevices extending out horizontally into a riverbed can be very effective gold-catchers, because the force of water can be enough to keep the upper part of the crevice clean of material, yet the shape and depth of the crevice may prevent gold from being swept or boiled out once it is inside.

Crevices running lengthwise with the flow of the stream or in a diagonal direction across the bed can be good gold traps or poor ones, depending upon the shape of the crevice and the set of circumstances covering each separate situation. For the most part, water force can get into a lengthwise crevice and prevent a great deal of gold from being trapped inside. However, this mostly depends upon the characteristics of the bedrock surface, and there are so many possible variables that it is no use trying to cover them all-such as the possibility of a large rock becoming lodged inside a lengthwise crevice, making its entire length a gold trap of bonanza dimensions. There is really no need to say much more about lengthwise-type crevices. Because if you are mining along and uncover one, you are going to clean it out to see what lies inside, anyway.

Potholes in the bedrock foundation of a streambed have a tendency to trap gold very well. These usually occur where the bedrock surface is deteriorating and some portions are coming apart faster than others, leaving holes which gold can drop into and thereafter be protected from the main force of water.

Bedrock dikes (upcroppings of a harder type of bedrock) protruding up through the floor of a streambed can make excellent gold traps in different ways, depending upon the direction of the dike. For example, if a dike protrudes up through the floor of a streambed and is slanted in a downstream direction, gold will usually become trapped behind the dike where it becomes shielded from the main force of the flow. A dike slanting in an upstream direction is more likely to trap gold in a little pocket just up in front.

Hairline cracks in the bedrock surface of a streambed often contain surprising amounts of gold. Sometimes you can take out pieces of gold that seem to be too large for the cracks that you find them inside of, and it leaves you wondering how they got there. Once in a while, a hairline crack will open up into a space which holds a nice little pocket of gold.

Hairline cracks can hold plenty of gold, and sometimes open up into small pockets.

How smooth the bedrock surface is has a great deal to do with how well its various irregularities will catch gold. Some types of bedrock, like granite for example, are extremely hard and tend to become pounded into a smooth and polished surface. Polished bedrock surfaces like this generally do not trap particles of gold nearly as well as the rough types of bedrock surfaces do. Also, polished bedrock, which sometimes contains large, deep “boil holes” (holes which have been bored into the bedrock by enormous amounts of water turbulence), is often an indication of too much turbulent water force to allow very much gold to settle there during flood storms.

Rougher types of bedrock, often being full of both large and small irregularities, have the kind of surface where many paying placer deposits are found. This kind of bedrock can be very hard and still maintain its roughness. Or it can be semi-decomposed. Either way, it can trap gold very well.

Rough bedrock surfaces tend to trap gold very well.

Basically, anywhere rough bedrock is situated so that its irregularities can slacken the force of water, in a location where gold will travel, is a likely place to find gold trapped.

Obstructions in a streambed can also cause the flow of water to slow down and can be the cause of a gold deposit, sometimes in front and sometimes to the rear of the obstruction. An outcropping of bedrock jutting out into a stream or river from one side can trap gold in various ways, depending upon the shape of the outcropping and the direction it protrudes into the stream. An outcropping extending out into the river in an upstream direction is most likely to trap gold in front of the outcropping where there is a lull in the water force. A gold deposit is more likely to be found on the downstream side of an outcropping which juts out into the river in a downstream direction, because that is where the force of the flow lets up.

LARGER GOLD TRAPS: PAY-STREAK AREAS

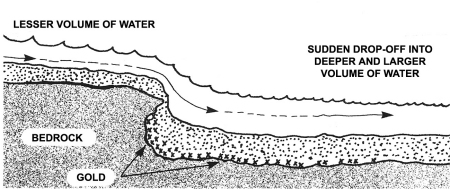

One of the most common locations within a stream or river to find a gold deposit is where the bedrock drops off suddenly to form a deep-water pool. Any place where a fixed volume of water suddenly flows into a much larger volume of water is a place where the flow may slow down. Wherever the flow of water in a streambed slows down during a major flood storm is a good place for gold to be dropped. And so it is not uncommon to find a sizable gold deposit in a streambed where there is a sudden drop-off into deeper water.

Any sudden drop-off into a deeper and larger volume of water is a likely spot to look for a sizable deposit of gold.

A waterfall is the extreme example of a sudden bedrock drop-off and can sometimes have a large deposit of gold at its base-but not always. Sometimes the water will plunge down into the hole of the falls and create so much turbulence that gold dropped into the hole during a storm can become ground up or boiled out. This is also potentially true of any other lesser sudden drop-off locations inside of a waterway.

On the other hand, sometimes large boulders can become trapped at the base of a falls and protect the gold from becoming ground up or boiled out by the turbulence. In this case the falls can become a bonanza.

In some waterfalls (or lesser sudden drop-off locations) the gold that has been boiled out will drop just outside of the hole, where the force of water has not yet had enough runway to pick up speed again-at least not enough to carry off much of the gold which arrives there.

Waterfalls are usually the territory of the suction dredger, because this type of gold trap usually deposits the gold underwater. Yet, this is not always the case. Sometimes during the low water periods of the year, some of the area below a falls can be exposed. There might be only a small amount of streambed to move in order to reach bedrock-where most of the gold is likely to be. The only dependable way to determine if gold will be present below a falls, or any other sudden drop-off location in a waterway, is to sample around and find out. Usually this is rather easy (unless you run into huge boulders); because if the area has been boiled out and swept clean of gold, often the bedrock will be exposed or have a layer of light sand and gravel on top. Again, this is not always true. Each falls has its own individual set of circumstances.

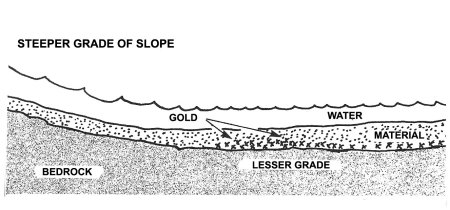

Another common location where a sizable gold deposit might be found is where the layout of the countryside causes the stream to run downhill at a rather steep grade for some distance and then suddenly it levels off. It is just below where the slope of the streambed levels off that the water flow will suddenly slow down during a major flood storm. This is where you are likely to find a concentration of gold. Areas like this are known for their very large deposits (pay-streaks).

The area just below where a streambed’s slope lessens often contains a good-sized gold deposit.

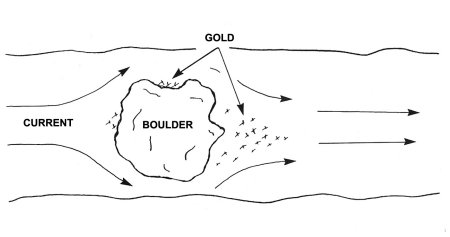

Boulders are another type of obstruction which can be in a riverbed and cause gold to drop out of a fast flow of water. Boulders are similar to gold in that the larger they are, the more water force it takes to move them. Sometimes during a storm, the force of water can pick up enough to sweep large amounts of streambed material and gold down across the bedrock. When this happens, the force may or may not be great enough to move the large boulders. A large boulder which is at rest in a stream, while a torrent of water and material is being swept past it during a large storm, will slow down the flow of the stream just in front, below and somewhere behind the boulder. This being the case, if the storm’s torrent happens to sweep gold near the boulder, some of the gold may concentrate where the slackening of current is at the time of the storm.

A boulder at rest in a streambed during a large storm might trap gold wherever it slows down the water force.

One thing to know about boulders is that they do not always have gold trapped around them. Whether or not a specific boulder will have a deposit of gold along with it depends greatly upon whether or not that boulder is in the direct path the gold took when it traveled through that particular section of streambed during earlier major flood storm periods.

THE PATH THAT GOLD FOLLOWS

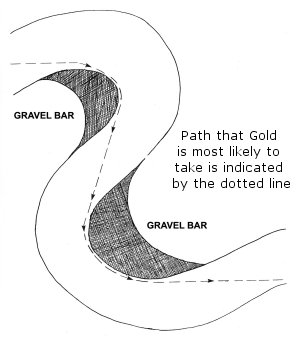

Because of its weight, gold tends to travel down along a streambed taking the path of least resistance. For the most part, this seems to be the shortest route possible between major bends in the stream.

Gold tends to follow the shortest route possible between any major changes in the direction of the stream or river.

Take note that the route the gold is taking rounds each curve towards the inside of the bends in the river. While this might not be the route gold always takes in a streambed, it is true that when it comes to curves, the majority of gold deposits are found towards the inside of bends. In comparison, very few are found towards the outside. Centrifugal force causes a much greater energy of flow to the outside of the bend. This creates less force towards the inside, which allows for gold to drop there.

Take note that the route the gold is taking rounds each curve towards the inside of the bends in the river. While this might not be the route gold always takes in a streambed, it is true that when it comes to curves, the majority of gold deposits are found towards the inside of bends. In comparison, very few are found towards the outside. Centrifugal force causes a much greater energy of flow to the outside of the bend. This creates less force towards the inside, which allows for gold to drop there.

It is important for you as a prospector to grasp the concept that under most conditions, gold tends to travel the shortest distance between the bends of a stream or river, and it also seems to deposit along the inside of the bends. Your best bet in prospecting is to direct your sampling activities towards areas which lie in the path that gold would most likely follow in its route downstream within the waterway. This requires an understanding of what effects the various changes in bedrock and the numerous obstructions will have on changing and directing the path of gold as it is pushed downstream during extreme high water periods. For example, if you are sampling for concentrations of gold around and behind boulders, you are better off to begin with the boulders lying in the path that gold would most likely take. This is likely to be more productive than just sampling boulders randomly in the streambed, no matter where they are located.

- Basics of Successful Gold Mining, Part 1

- Basics of Successful Gold Mining, Part 2

- Basics of Successful Gold Mining, Part 3

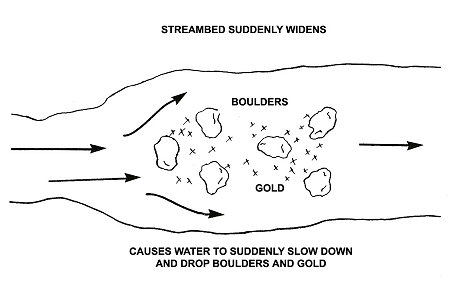

WHERE THE STREAMBED WIDENS

Another situation within a stream or river where there is often a sizable concentration of gold (pay-streak) is where the stream runs narrow or at a certain general width for some distance and then suddenly opens up into a wider portion of streambed. Where the streambed widens, the water flow will generally slow down, because the streambed allows for a larger volume of water in such a location-especially during extreme high water periods. Where water force slows down is a likely place for gold to drop.

Anywhere that a streambed suddenly widens enough to slow the force of the

stream during high water periods is a likely place to find a deposit of gold.

Notice that some boulders will also drop where the water force is suddenly slowed down. Boulders are similar to gold in that it takes a tremendous amount of force to push them along. Wherever that force lets up enough, the boulders will drop. So boulders are often found in the same areas where large amounts of gold are deposited. But gold is not always found where boulders are dropped. This is because there are so many boulders within the waterway, and the majority of them probably do not continuously follow the same route that gold generally takes. Nevertheless, it is well to take note that those places where boulders do get hung up, which are on the same route that gold follows down the waterway, are generally good places to direct some of your sampling activities.

ANCIENT RIVERS

About two million years ago, towards the end of the Tertiary geological time period, the mountain systems in the western United States underwent a tremendous amount of faulting and twisting, changing the character of the mountains into much of how they look today. It was during the same period when the present drainage system of streams, creeks and rivers were formed, which runs pretty-much in a westerly direction.

Prior to that, there was a vastly different river system, which generally ran in a southerly direction. These were the old streambeds which ran throughout much of the Tertiary geologic time period, and so are called “tertiary channels” or“ancient rivers.” The ancient rivers ran for millions of years, during which time an enormous amount of erosion took place, washing very substantial amounts of gold into the rivers from the exposed rich lode deposits.

The major changes occurring towards the end of that period, which rearranged the mountains and formed the present drainage systems, left portions of the ancient channels strewn about. Some portions were placed on top of the present mountains. Some were left out in the desert areas. And some portions were left close to, and crossed by, the present drainage system.

Some geologists have argued that most of the gold in today’s river systems is not gold that has eroded more recently from lode deposits, but gold that was eroded out of the old ancient riverbeds where they have been crossed by the present river systems.

The ancient channels, where they have been discovered and mined, have often proven to be extremely rich in gold deposits. In fact, many of the richest bonanzas that have been found in today’s river systems have been discovered directly downstream from where they have crossed the ancient streambed gravels. Other areas which have proven to be very rich in today’s river systems have been found close to the old channels, where a few million years of erosion have caused some of the channel and its gold to be eroded into the present streambeds.

Ancient channels (benches) are well known for their very rich bottom stratum. This stratum is sometimes of a deep blue color; and indeed the rich blue color, when encountered, is one of the most certain indicators that ancient gravels are present. This bottom stratum of the ancient gravels was referred to by the old-timers as the “blue lead”, probably because they followed its path all over the west wherever it led them.

Ancient blue gravels usually oxidize and turn a rusty reddish brown color after being dug up and exposed to the atmosphere. They can be very hard and compacted, but are not always that way.

Running into blue gravel at the bottom of a streambed does not necessarily mean that you have located an ancient channel. But it is possible that you have located some ancient gravel (deposited there from somewhere else) which might have a rich pay-streak associated with them.

Most of the high benches that you will find up alongside today’s rivers and streams, and sometimes a fair distance away, but which travel generally in the same direction, are not Tertiary channels. They are more likely the earlier remnants of the present rivers and streams. These old streambeds are referred to by geologists as “Pleistocene channels.” They were formed and ran during the time period between 10,000 years ago and about a million and a half years ago — which was the earlier part of the Quaternary Period, known as the Pleistocene epoch. Some high benches that rest alongside the present streams and rivers were formed since the passing of the Pleistocene epoch. These are referred to as “Recent benches,” having been formed during the “Recent epoch” (present epoch).

Some of these benches, either Pleistocene or Recent, are quite extensive in size. Dry streambeds are scattered about all over gold country, some which have already been mined, but many are still untouched.

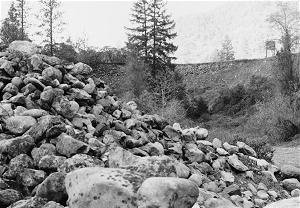

Usually, all that is left of a bench after it has been mined are rock piles. Notice in the picture that part of the non-mined streambed is in the background, behind the trees.

Usually all that is left of a high bench after it has been mined are piles of the larger-sized streambed rocks and boulders.

Most of the hydraulic mining operations which operated during the early to mid-1900’s were directed at high benches.“Hydraulic mining” was done by directing a large volume of water, under great pressure, at a streambed to erode its gravels out of the bed and through recovery systems, where the gold would be trapped.

A hydraulic mining operation. Photo courtesy of Siskiyou County Historical Museum.

So some bench gravels have been mined, but many of them still remain intact. While the Pleistocene and Recent benches are generally not as rich in gold content as were the Tertiary’s, it still remains true that an enormous amount of gold washed down into these old channels when they were active. They are pretty darn rich in some areas, and pay rather consistently in others. Also, any and all gold that has ever washed down into an old bench which has yet to be mined still remains there today.

FLOOD GOLD

A large percentage of the gold found in today’s creeks and rivers has been washed down into them out of the higher bench deposits by the erosive effects of storms and time. A certain amount of gold is being washed downstream in any river located in gold country at all times, even if only microscopic in size.

The larger a piece of gold is, the more water force that it takes to move it downstream in a riverbed. The amount of water force it takes to move a significant amount of gold in a riverbed is usually enough force to also move the streambed, too. This would allow the gold to work its way quickly down to the bedrock, where it can become trapped in the various irregularities.

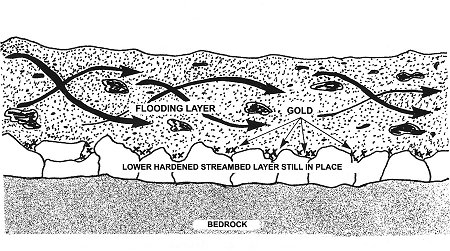

Some streambeds contain a high mineral content and grow very hard after being in place for an extended period of time.

Sometimes a storm will have enough force to move large amounts of gold, but will only move a portion of the entire streambed, leaving a lower stratum in place in some locations. When this happens, the gold moving along at the bottom of the flooding layer can become trapped by the irregularities of the unmoving (“false bedrock”) streambed layer lying underneath. The rocks in a stable lower stratum can act as natural gold traps.

Flood gold is that gold which rests inside and at the bottom of a flooding layer.

Different streambed layers, caused by major flood storms, are referred to as “flood layers.” The flood layers within a streambed, if present, are easily distinguished because they are usually of a different color, consistency and hardness from the other layers of material within the streambed. That gold found at the bottom of or throughout a flood layer is often referred to as “flood gold.” Sometimes, the bottom of a flood layer will contain substantially more gold than is present on bedrock. Sometimes, when more than one flood layer is present in a streambed, there will be more than one layer of flood gold present, too.

The larger that a piece of gold is, the faster it will work its way down towards the bottom of a layer of material as it is being washed downstream during a storm. Finer-sized pieces of gold might not work their way down through a flood layer at all, but might remain disbursed up in the material.

So you can run across a flood layer which has a line of the heavier pieces of gold along its bottom edge, or a flood layer which contains a large amount of fine gold dispersed throughout the entire layer. You can also run across a flood layer which contains a lot of fine gold dispersed throughout, in addition to a line of heavier gold along the bottom edge.

Not all flood layers contain gold in paying quantities for a small-scale mining program. But in gold country, all flood layers do seem to contain gold in some quantity, even if only microscopic in size.

GRAVEL BAR PLACERS

Gravel bars located in streambeds flowing through gold country, especially the ones located towards the inside of bends, tend to collect a lot of flood gold, and sometimes in paying quantities even for the smaller-sized operations. The flood gold in bar placers is sometimes consistently distributed throughout the entire gravel bar. Sometimes the lower-end of a gravel bar is not as rich as the head of the bar, but the gold there can be more uniformly dispersed throughout the material.

FALSE BEDROCK

Once in a while a prospector will uncover an extremely hard layer of streambed material located just above the bedrock and mistake the layer for bedrock because of its hardness. A hard layer is often referred to as “false bedrock.” Such a layer can consist of streambed material, or of volcanic flows which have laid down and hardened on top of bedrock, or it can consist of any kind of mineral deposit which has hardened over time on top of the true bedrock.

There can be a good-paying gold deposit underneath a false bedrock layer. But when there is, it is usually rather difficult to get at.

Actually, for the purpose of sampling, the top of every different storm layer within a streambed should be considered a“false bedrock” and can be a surface-area for gold to become trapped out of the flood layer which laid down on top.

- Here is where you can buy a sample of natural gold.

- Here is where you can buy Gold Prospecting Equipment & Supplies.

- More about Gold

- How to Sample for Gold

- Schedule of Events

- Books & Videos by Dave McCracken