By Ron Wendt

“I Remember Seeing The Miners Coming In With Bags Full Of Gold…”

The old man leaned against his shovel and wiped his brow as the hot interior Alaska sun beat down upon him. He was a veteran of the gold rush. He had missed too many boats and never quite made it back out of Alaska. It had been over sixty years since he had walked the streets of Seattle, where he first caught a boat to head north to the Klondike. It was the gold that kept him here, and his sluice box, shovel, and gold pan were an integral part of him.

The old man leaned against his shovel and wiped his brow as the hot interior Alaska sun beat down upon him. He was a veteran of the gold rush. He had missed too many boats and never quite made it back out of Alaska. It had been over sixty years since he had walked the streets of Seattle, where he first caught a boat to head north to the Klondike. It was the gold that kept him here, and his sluice box, shovel, and gold pan were an integral part of him.

He looked at me and never said a word. Even at my age in the early 1960’s, I could tell he was not having any fun. It was a tedious job for him. He shafted to bedrock during the winter and sluiced in the summer. As my father used to tell me, “He made enough gold to buy beans.” The old man was content with his life in the wilderness where he answered to no one; only the occasional camp robber or raven would land nearby, begging for a few scraps of food the miner had.

Even in the late 50’s, as a small boy, I remember seeing the miners coming in from the Fortymile River with bags of gold, begging for someone to buy it just so they could feed themselves. One miner had a cake pan full of nuggets he tried to peddle. He wanted $500 for the whole pan, but my father could only afford to buy a few choice nuggets from him at a cheap price.

My first homemade sluice box was built from old photos, some advice (some poor and some good), a few aged pieces of plywood and two-by-fours, wooden slats for riffles and burlap to catch the gold. At sixteen, I had visions of gold, just like any other person would after reading Jack London’s books and other stories about the gold rush. Having been raised in the gold camps of the Circle Mining district in eastern Alaska, I had watched many miners, including my father, extract gold with sluices and gold pans.

My first homemade sluice box was built from old photos, some advice (some poor and some good), a few aged pieces of plywood and two-by-fours, wooden slats for riffles and burlap to catch the gold. At sixteen, I had visions of gold, just like any other person would after reading Jack London’s books and other stories about the gold rush. Having been raised in the gold camps of the Circle Mining district in eastern Alaska, I had watched many miners, including my father, extract gold with sluices and gold pans.

Here I was in the Yentna River area near the Alaska Range, with a water-logged wooden sluice box, trying to make my first big strike. Believe me, there is nothing worse than trying to move around water-soaked wood! With the help of a more seasoned prospector, we located a bench of pay-dirt where a false bedrock of clay rose up out of Twin Creek. Through some trial and error, I figured out that the gold was in the clay. After shoveling tons of dirt and clay into my sluice, I soon discovered that I was not breaking up the clay enough and was losing quite a lot of gold with the tailings.

- Basics of Successful Gold Mining, Part 1

- The Basics of Successful Gold Mining, Part 2

- Basics of Successful Gold Mining, Part 3

Between shoveling into the head, and raking rocks through the sluice, just as I watched that old man do years before, I was able to recover six ounces of gold for the two mosquito-infested, rain-soaked months that I worked this bench. Though it wasn’t a fortune, I didn’t care; I felt as happy as that old-timer probably did when he just got started years before. I have learned a lot since then, but I still value all of the early golden lessons taught to me by those old sourdoughs.

Eventually, I graduated to the wonderful world of aluminum. The aluminum sluice has been a great blessing to the modern day prospector. They are great for back-packing and throwing around in the back of the pickup. They don’t break; and if you learn to master them, they will reward you with great recovery results.

Some places in Alaska are pretty remote. Not always can one put a suction dredge in just anywhere. It is so much easier to walk into the hills with a four-foot, fifteen-pound sluice box, than hauling a 200-pound suction dredge over hummocks and through alders. Each piece of equipment has its place.

I have always recommended that if you are going to get into prospecting, start out small. Start with a gold pan, then sluice with pick & shovel, then eventually get into a dredge system. From there, who knows–maybe a D-8 will be your next tool!

I have found that if you are going for the gold, like most everything, unless you are pretty lucky, you will not strike it rich right off. Finding the high-grade gold deposits is something that gradually happens as you learn the right approach.

I have also found out that when new prospectors start off all gung-ho into this business, hauling in big equipment where there is not much gold, they usually lose interest real fast. After two or three outings, a few thousand dollars of investment and no return, they get discouraged and quit.

I suggest it is better to start small and learn the art of prospecting. Shoveling into portable sluice is an excellent, economical way to learn the basics of finding gold.

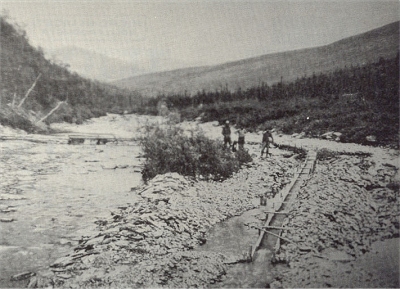

In the old days, the sluice boxes were usually 12-to-14 inches wide, pieced together in telescoping sections, with pole riffles. The boxes were set at an average grade of six inches to the twelve-foot box. Water was directed to the head of the sluice from a long flume or a canvas hose coming from a dam. As in today’s sluicing operations, the name of the game was production, shoveling the most pay-dirt into the sluice. With long lines of sluice boxes, the kind you see in the old photographs, miners would try to set up the sluices so there would be six feet open on either side of the boxes. The lighter material was shoveled in while the larger rocks were placed on bedrock and washed later on.

During those days, shoveling-duty varied with the nature of the gravel and bedrock, how far pay-dirt had to be lifted to the sluice from the excavation, and the person’s capability to work. Under ideal sluicing conditions, a shoveler could feed as much as 2 ½-to-10 cubic yards of gravel in 10 hours.

In 1905 on Anvil Creek near Nome, there was one elaborate set of sluice boxes set up on bedrock. Five strings of sluices were shoveled into 24 hours a day by 120 shovelers. They were able to process an average of 1,080 cubic yards of pay-dirt per day during this time.

The good thing about prospecting with a sluice box is that you can process a lot of material just using a good No.2 shovel and a sharp pick. A sluice is an excellent way to scout out good future prospects.

I have heard some pretty interesting stories about sluice boxes. One classic story I remember happened up on the Koyokuk River around 1914. A prospector made a big strike; but all he had was a gold pan, shovel and an ax. So he cut down a tree, split-out a four-foot piece, carving out a set of riffles along the bottom edge. Although this was indeed very crude, the prospector found enough gold in two days to party in San Francisco for four months!

When sluicing with a portable aluminum sluice, there are several key factors to be aware of:

1. Water-speed is critical to gold recovery. Some gold can be lost out the end if the water is too swift-flowing through the box. If the water-flow is too slow, the heavy rocks, black sand and/or garnets can clog the riffles and the gold can wash out. So it is critical to learn water-flow. In my own experience, water-flow in the sluice should be no more than three inches deep with a flow that will tumble golf ball-sized rocks out the end.

2. It is important to keep the sluice box raked out after one or two shovelfuls of pay-dirt are fed into the head of the box. Allowing too much material to pile up in the sluice can also cause erratic water flow in the sluice. This can cause a gold loss, too.

3. The sluice should be on a slight slope. Most streams have a natural slope as they flow along. But there are times when the sluice needs to be adjusted to increase water-flow, especially in wider, deeper water. Sometimes, water-flow can be increased through your sluice simply by raising up the head of the sluice; and, whenever needed, using rocks underneath and around the sluice to dirvert more water.

For under $200, a prospector can be outfitted with an aluminum sluice, gold pan, pick and shovel. The sluice is one of the handiest prospecting tools next to the gold pan.

- Here is where you can buy Gold Prospecting Equipment & Supplies.

- Here is where you can buy a sample of natural gold.

- More about surface mining

- More about gold dredging

- More about how to prospect for gold

- Schedule of Events

- Best-selling Books & Videos on Gold Prospecting