By Dave McCracken

You don’t know what frustration is until you have gone back and forth from your dredge to your dredge hole three or four—or eight—times trying to knock out a single plug-up!

One of the main impediments to production in gold dredging is the occurrence of plug-ups in the power jet and/or suction hose. A plug-up is caused when a single rock, or a combination of rocks, lodge in the suction hose or power jet, which then prevent further material from being sucked up.

One of the main impediments to production in gold dredging is the occurrence of plug-ups in the power jet and/or suction hose. A plug-up is caused when a single rock, or a combination of rocks, lodge in the suction hose or power jet, which then prevent further material from being sucked up.

Beginners are especially plagued with many, many plug-ups, because they have not yet learned which types of rocks, or which combinations of rocks, to avoid sucking up the nozzle. Everybody that dredges must get through this part of the learning curve.

When possible, an experienced gold dredger will watch to see what kind of rocks caused a plug-up every time he or she will get one. Beginners should do this as well. This way, after a while, you gain an understanding of which type of rocks and combinations to avoid putting through the nozzle.

For the most part, the rocks to avoid sucking up are those that are just large enough to fit in the nozzle that are sharp and angular, or that are shaped in such a way that if turned sideways, they could possibly lodge in the suction hose or jet.

Sucking up a larger round rock, just after a long-thin rock, or just after a medium-sized flat rock, is just asking for a plug-up. The reason for this is because the round rock, having more surface area, will move up the hose faster than the flat rock. So the round rock can catch up and possibly cause the flat rock to turn and lodge. Generally, we avoid sucking up large flat rocks altogether.

Generally, we avoid sucking up large flat rocks altogether. Just like there is a system of knowing how to avoid plug-ups, there is also a system for removing plug-ups quickly.

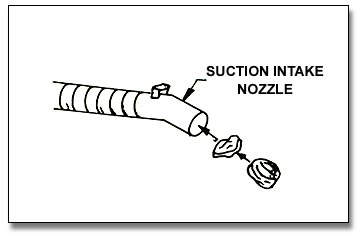

Many plug-ups occur in the power jet. These are generally caused for two reasons (in addition to sucking up the wrong rocks). The first is because of a design-flaw. Many power jets are smaller in diameter than the inside of the suction hose. Where the larger-sized suction hose meets the smaller-sized jet, there is a restriction which can cause rocks to lodge.

Many plug-ups occur in the power jet. These are generally caused for two reasons (in addition to sucking up the wrong rocks). The first is because of a design-flaw. Many power jets are smaller in diameter than the inside of the suction hose. Where the larger-sized suction hose meets the smaller-sized jet, there is a restriction which can cause rocks to lodge.

The other reason for plugs in the power jet is further up just beyond the inductor(s). High-pressure water comes from the side into the main jet tube from one or more inductors which can spin a rock just right to make it lodge.

Once you gain some experience in dredging, you can often tell from the feel of the plug-up when you get it whether the plug-up is in the hose or the jet. Jet plug-ups are usually very sudden; you can feel them “slam”, with a sudden complete loss of suction. Hose plug-ups sometimes leave you with some smaller amount of suction at the nozzle.

The first thing to remember with a plug-up is to stop sucking material into the suction nozzle as soon as you realize you have one!

All of us, sooner or later, experience the joy of loading a suction hose full of rocks and gravel. But you haven’t experienced life to the fullest until you have had the opportunity to do this with a 12-inch dredge! A plug-up is much easier to remove if you have not sucked up a bunch of additional rocks and gravel to complicate the problem.

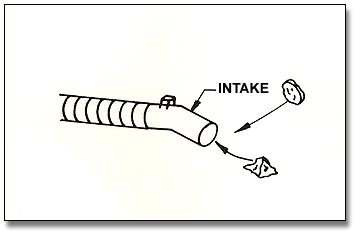

When you get a plug-up in the suction hose, sometimes you can free it up simply by yanking forward on the hose, or by popping your hand over the intake of the suction nozzle. If there is still some suction, sometimes purging air from your regulator into the nozzle will help free the plug-up. When I get a plug-up, I will do this a few times, and then set down the nozzle (where it will not suck up further material) and move rocks out of my way for a little while to see if the plug-up will free itself.

I always like to keep the outside of my suction hose nice and clean. This means using a good wash brush to clean the algae off once every two weeks or so. Or, you can disconnect your suction hose from the dredge and clean it with a pressure washer. The good thing about a clean hose is that you can look into it for plug-ups as you move towards your dredge to knock the plug-up out of the jet. Sometimes, when you think it is a jet plug-up, you discover that the plug-up is in the hose. With a clean, clear hose, it is usually pretty easy to spot the plug-up quickly. This all saves time, energy and frustration.

When leaving your dredge hole to find a plug-up, always leave the suction nozzle positioned so that it will not suck up additional material, or will not get sucked against a larger cobble or boulder as the plug-up is being removed. As the plug-up is being freed, you need water movement through the hose to help carry the rocks which caused the obstruction out of the system. Sometimes, the offensive rocks free-up and then cause another obstruction further up the hose. On tough obstructions, I will generally follow the rocks up the hose until I am certain they are through the system. You can hear the rocks rattle up through your metal power jet if you are listening.

Another reason for leaving your suction nozzle so it will not get blocked by a cobble or boulder, is that when you are probing the power jet for the plug-up from the surface, you are paying attention to how much water is flowing through the sluice box. A plug-up slows the water down. When the obstruction is freed up, more water consequently flows through the box. If you are watching, you will then see the offensive rocks flow into the sluice (where you can take a look at them). This is, unless the suction nozzle gets sucked up against something down in your dredge hole which prevents forceful water movement through the suction hose.

It is really important to get this right. You don’t know what aggravation is until you have gone back and forth from your dredge hole to your dredge three or four—or eight—times trying to knock out a single plug-up!

You need to develop a feel for probing the jet from the surface for plug-ups. This is done with a “jam rod” (Also sometimes referred to as the “plugger pole.”).

What I mean by getting a feel for probing, is that you have to learn to feel around and find where the obstruction is in the jet.

Some beginners start off thinking the key is to simply slam the jam rod down into the jet over and over again—the deeper the better. This does absolutely no good if the plug-up is further up into the jet and the rod is just bypassing it. Sometimes the jam rod goes down into the jet, through the rocks causing the obstruction. The person comes to the surface, slams the jam rod deep into the jet a few times, feels no plug-up, decides the obstruction is in the hose, goes back down and follows the hose back to the dredge hole, follows the hose back up to the dredge, jams the rod deep into the jet, etc., etc., and finally decides there is something wrong with the pump! This is all part of the learning curve, and can be very frustrating.

What I mean by getting a feel for probing, is that you have to learn to feel around and find where the obstruction is in the jet. Some beginners start off thinking the key is to simply slam the jam rod down into the jet over and over again—the deeper the better. This does absolutely no good if the plug-up is further up into the jet. Sometimes the jam rod goes down into the jet, through the rocks causing the obstruction. The person comes to the surface, slams the jam rod deep into the jet a few times, feels no plug-up, decides the obstruction is in the hose, goes back down and follows the hose back to the dredge hole, follows the hose back up to the dredge, jams the rod deep into the jet, etc., etc., and finally decides there is something wrong with the pump!

And, this is why it is important to learn to get a feel for probing. I do this by probing down the jet about a foot at a time, probing at different angles, feeling for the obstruction. The obstruction is that solid-something that the jam rod touches as you are feeling around in the jet. Sometimes, it is barely a nudge as the rod slides past the obstruction. So you really need to pay attention when probing!

Once I feel the obstruction, I direct the jamming action to free it up. If smacking on the obstruction does not free it, try again after turning the engine down to idle.

Some experienced dredgers weld a “T” onto the upper-end of their jam rods. This is for the simple reason of avoiding the additional aggravation of having to remove the suction hose to recover your jam rod if it slips from your hand and slides down the jet and suction hose! If you make the T-handle narrower than the diameter of your power jet, you can turn the jam rod around and use the T-handle to help you find the occasional elusive rocks that lodge in the power jet.

It is also a good idea to have a bolt or some other solid rod material welded onto the probing-end of your jam rod. Otherwise, the pounding action can cause the probing-end to flair out. This causes problems when you jam the rod down through an obstruction, and the flared portion gets stuck when you are trying to pull it back out. The probing-end of your jam rod should be a smooth continuation of the rod itself.

If a plug-up is found in the suction hose, it can usually be freed-up by tapping against it with a smooth cobble from your cobble pile. If you look over the obstruction, you can usually see the best angles to tap against the obstruction. If one angle does not work, perhaps another angle will free it up. If the obstruction does not free up easily, the answer is not to beat your suction hose full of holes! The next step is to turn your dredge engine down all the way to an idle. This releases the heavy suction pressure holding the plug-up in place. Once the engine is idled down, you can usually tap the obstruction free with little difficulty. Then, by turning up the engine, often the rocks which caused the obstruction will get sucked through the system. Sometimes, they will also plug-up the hose or jet again—in which case, you go through the process all over again. This same procedure is used also in jet plug-ups.

If this procedure does not work on a hose plug-up, the next step is to remove the water from the hose. This can be done by lifting the suction nozzle out of the water while the engine is running at idle, or at just enough throttle to pump the water out of the suction hose. With no water in the hose, an obstruction is usually very easy to free up. In this case, however, it is wise to shake the rocks completely down the hose and out of the nozzle—to be sure you are finished with them. Here is a helpful hint: Remember to then toss the offensive rocks out of your hole, so you do not suck them right back up again when the dredge’s throttle is turned back up!

When a really difficult plug-up is in the suction hose near the jet, sometimes it is necessary to disconnect the suction hose and pull it up onto the bank to remove the obstruction. This is only on very difficult obstructions. If you are paying attention to what you are sucking through the nozzle, you should not be burdened with this chore very often!

All of this unnecessary additional work will prompt you to pay more attention to what you are feeding into the nozzle! I have spent plenty of time watching beginners invest more than 50% of their day just on freeing plug-ups!

All of this unnecessary additional work will prompt you to pay more attention to what you are feeding into the nozzle! I have spent plenty of time watching beginners invest more than 50% of their day just on freeing plug-ups!

Several years ago, in an effort to enhance production, we developed oversize power-jets and exterior suction hose clamps. In this way, the suction hose fits into a jet tube which is slightly larger in size than the hose. This can eliminate 95 percent or more of the plug-ups which a dredger will get on a normal day. Some of the dredge manufacturers are now creating dredges with oversized jet tubes and exterior suction hose clamps—which is one of the best things that has happened for suction dredges in quite some time.

Caution: just because a dredge has an exterior suction hose clamp does not mean that the jet is larger than the hose. You have to look closely and measure to be certain. If the mechanism has any part of the jet smaller in diameter than the inside of the suction hose, you are going to get plug-ups there no matter how careful you are at the nozzle. What I am saying is that an oversized jet tube for a 5-inch dredge should have an inside diameter greater than 5-inches.

Team work on removing plug-ups can be very efficient when two or more dredgers are working together. When I am nozzling and get a plug-up, I usually hand the nozzle to one of my rock men, or send the rock man up to find the plug-up. Once the plug-up is removed, material is immediately sucked into the nozzle. This creates a signal to the person trying to locate the obstruction that it has been cleared. If no material is moving through the hose and sluice box, it is a definite signal that the obstruction still exists somewhere in the system—or that the partner has fallen asleep and lost track of what is going on (It is a good thing that you cannot hear miners when they get frustrated at each other while underwater).

While sampling, or during production dredging, the end result is directly proportional to how much material you are able to feed into the suction nozzle. Plug-ups play a big part in this; because while you are spending time freeing up obstructions, you are not sucking up pay-dirt!

If you are having problems with plug-ups, sometimes you can improve production by just slowing down a little.

The real key is in oversized jets. The amount of work to build and install one on your dredge is small compared to the amount of energy and time you will spend knocking plug-ups out of your jet during the course of a mining season!

Everyone gets some plug-ups. The thing to do is improve your control of the nozzle to the point where you only get a few (or none) each day.

- Here is where you can buy a sample of natural gold.

- Here is where you can buy Gold Prospecting Equipment & Supplies.

- More About Gold Prospecting

- More Gold Mining Adventures

- Schedule of Events

- Best-selling Books & DVD’s on this Subject