BY STEPHEN SOWN

ENGLAND’S HUNT FOR THE NORTHWEST PASSAGE SPARKED THE FIRST GOLD RUSH — AND, POSSIBLY THE FIRST GOLD SCAM!

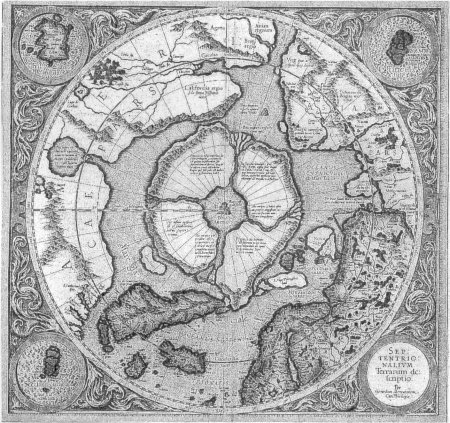

“Chart of the North Pole, ” by Gerhard Mercato1; 1595, depicting lands which could not be accurately shown on a regular projection. It not only includes errors of the standard chart, but an imagined view of the North Pole based on Marco Polo’s writings of the 13th century.

“Chart of the North Pole, ” by Gerhard Mercato1; 1595, depicting lands which could not be accurately shown on a regular projection. It not only includes errors of the standard chart, but an imagined view of the North Pole based on Marco Polo’s writings of the 13th century.

When Queen Elizabeth ascended the throne of England in 1558, she began a new age of northern exploration at a time when mariners were rewarded for daring, outrageous, risky and (possibly) illegal behavior. It was an age where, from a European point bf view, anything was possible–a whole New World had just been found. Surely a sea route to the Orient was possible.

Martin Frobisher was the quintessential, swashbuckling privateer of the Elizabethan age. He was also a well known pirate, sanctioned by Queen Elizabeth. Although arrested on at least four occasions on charges of high-sea piracy, he was only mildly chastised, as were other notorious English corsairs of the 16th century. Piracy was legal in England, provided it was directed against Spanish and Portuguese vessels. In fact, Elizabeth and many others in the court invested in the plundering expeditions of the bold entrepreneurs.

The discovery of the Northwest Passage offered glory, wealth, and prestige; it also offered cruel hardships, and perhaps death. Frobisher was definitely the man for the job–and Michael Lok knew it. Lok, a high-class promoter, gambler, entrepreneur and (perhaps) swindler provided both financial and political support for Frobisher’s scheme. To secure financial support, Lok went to great efforts to alter the public’s perception of Frobisher from a cunning pirrate into a romantic court gallant. He commissioned a portrait, and enlisted troubadours to compose ballads to praise his valiant exploits.

In 1576, Frobisher made the first of three historic voyages to “Frobisher’s traits” on Baffin Island. He sailed in two small vessels, approximately 25 tons each, and a small pinnacle too insignificant to be given a name. Only one of the ships, however, completed the Atlantic crossing without difficulty. Near the shores of Greenland, the smallest of the vessels, and her four men, floundered during a violent North Atlantic storm, and the sailors were sucked to their doom. A second vessel, unable to locate the others after the storm, returned to England claiming Frobisher had been drowned. But Frobisher’s flagship was not destroyed by the Atlantic storms.

Frobisher, who had vowed “to make a sacrifice unto Gold of his life rather than return home without the discovery of Cathay,” and eighteen surviving crew continued to search for the elusive Northwest Passage. They believed they had found it when they sailed into what is today known as Frobisher Bay. It was Frobisher’s belief that the land on his left as he sailed the “Straight” was the main continent of North America, while the land on his right was none other than Asia. Asia and North America had one important thing in common; mosquitoes. Frobisher was greatly irritated by these creatures, which were described as “a kind of small fly or knat that stingeth and offendeth so fiercely that the place where they bite shortly after swelleth and itcheth very sore.”

Frobisher also encountered foreign people while ashore on Baffin Island. George Bet commented on the Baffin Islanders: “these people are in nature very subtle and sharp-witted. They are ready to conceive our meaning by signs, and to make answer, well to be understood again. If they have not seen the thing whereof you ask them, they will cover their eyes with their hands, as if to say, it hath been hid from their sight. If they understand you not wherof you ask them, they will stop their ears. They will teach us the names of each thing in their language which we desire to learn, and are apt to learn anything of us. They delight in music above measure, and will keep time and stroke to any tune which you shall sing, both with their voice, hand and feet, and will sing the same tune aptly after you. They will row with our oars in our boats, and keep a true stroke with our mariners, and seem to take a great delight therein.”

Although the two peoples exchanged gifts and gestures of friendship, relations between them were not consistently harmonious. Five English sailors were either captured (or mutinied while ashore with the ship’s boat) and were never heard from again. In retribution for this perceived act of violence Frobisher lured one unfortunate Eskimo closer to the English ship by ringing a bell, and then “suddenly, by main force of strength, plucked both the man and his light boat out of the sea and into the ship in a trice.”

While being hauled aboard the ship the Inuit, who died shortly after reaching London, bit off his tongue and so was incapable of revealing the location of the five missing sailors.

Frobisher and his crew immediately departed the barren, rocky island for England with their captured “Strange man of Cathay.” They were cheerfully welcomed. Michael Lok paraded the man and his boat around London and the surrounding countryside.

Flowers and grass were some of the foreign plants proudly displayed. Most importantly, however, a small black stone was returned to England. This stone “glistened with a bright marquisette of gold” when held near to a fire.

“Englishmen in a Skirmish with Eskimos” by John White, 1585-93

“Englishmen in a Skirmish with Eskimos” by John White, 1585-93

When an unscrupulous Italian assayer identified the substance as gold, the Northwest Passage was promptly forgotten and the Cathay Company was hastily formed–with the prime objective of mining the golden ore from Baffin Island. A second naval expedition was immediately outfitted and departed for “Asia” in 1577.

While digging for gold on Baffin Island, Frobisher and his crew were again involved in violent confrontations with the local people. John White, an artist who traveled with Frobisher, preserved for posterity one such battle at “Bloody Point” in Frobisher Bay. Six Inuit were shot dead and one English sailor was pierced with an arrow. Frobisher again attempted to locate his five lost seamen from the previous year and; failing, he left them a letter (written in English) audaciously threatening that “if they deliver you not, I will not leave a man alive in their Country.” Frobisher settled his vengeful urge with the kidnapping of a young Inuit family. Master Dionise Settle, chronographer of this expedition, reported that “the two women not being apt to escape as the men were, the one for her age, and the other being incombred with a young child, we tooke. The old wretch, whom divers of our Saylers supposed to be either a devil, or a witch, had her buskins plucked off, to see if she was cloven footed, and her rougly hew and deformity we let her go: the young woman and the child we brought away.” Both died quickly in England.

In the fall of the same year, Frobisher returned with 200 tons of black lumpy ore, the so-called “gold” of Frobisher’s Straits. The expedition received a jubilant welcome in London. Frobisher was awarded the lofty title of “High Admiral of Cathay.”

Frobisher again sailed for Baffin Island in 1578-before the true nature of the black ore could be determined. The “High Admiral” captained a flotilla of 15 ships, the largest to assemble in the North Atlantic until World War II. As well as attempting to gamer the golden nuggets of Baffin Island, the expedition had provisions for the first English colony in North America, and the first missionary, Reverend Mr. Wolfall. Wolfall’s objective was to convert what he believed to be the cruel and ignorant heathen of Asia to the enlightened doctrine of his own philosophy.

Unfortunately, a violent storm had the disastrous effect of grinding and pummeling the flotilla, sinking many of the supply ships before they reached Baffin Island. Although plans for the colony were postponed, the remaining vessels continued with the mining operation. Another staggering quantity of black ore was hauled back to England.

Reverend Mr. Wolfal1 was not so successful in his endeavors. He could find no heathens to convert due to their timidity, no doubt stemming from Frobisher’s treacherous and violent behavior during previous years. With plans for the colony abandoned, Wolfall returned to England with the remaining ships.

Disgrace awaited the haggard survivors of the voyage. During their absence, it was determined that absolutely no gold could be alchemized from any of the ore returned the previous year. The “Asian gold” was worthless. Michael Lok was in financial trouble. Not only had he lost his own investment in the Arctic scandal, but numerous creditors’ demanded repayment of their investments.

- Here is where you can buy a sample of natural gold.

- Here is where you can buy a basic gold prospecting kit.

- More about the history of gold

- More about how to prospect for gold

- Gold mining adventures

- Schedule of Events

- Books and Videos by Dave McCracken.