Story by Marcy Stumpf/Foley

Photos by Norm Frain

As I finished the last of the dinner dishes under my tarp “roof,” I looked out over our mining camp, nestled in the bottom of a steep, narrow, forested canyon. Camped in tents along the bank of our sparkling clear creek, we seemed very small in the miles of wilderness that surrounded us. We were three families, eleven people in all, with children ranging from five years to 21, and this was our first summer together as partners in a mining claim. Wet suits were drying on the clothesline, and the final clean-up of the day’s gold was done, as we all hurried to finish the last of our chores. The other women also washed dishes, the children joked and teased as they returned with fallen wood for our campfire, and the men finished minor equipment repairs and refilled solar shower bags and water buckets for the next day’s use. The sun was leaving our canyon, taking its warmth. “Our” blue heron was making his evening flight down our canyon as we gathered around our campfire.

As I finished the last of the dinner dishes under my tarp “roof,” I looked out over our mining camp, nestled in the bottom of a steep, narrow, forested canyon. Camped in tents along the bank of our sparkling clear creek, we seemed very small in the miles of wilderness that surrounded us. We were three families, eleven people in all, with children ranging from five years to 21, and this was our first summer together as partners in a mining claim. Wet suits were drying on the clothesline, and the final clean-up of the day’s gold was done, as we all hurried to finish the last of our chores. The other women also washed dishes, the children joked and teased as they returned with fallen wood for our campfire, and the men finished minor equipment repairs and refilled solar shower bags and water buckets for the next day’s use. The sun was leaving our canyon, taking its warmth. “Our” blue heron was making his evening flight down our canyon as we gathered around our campfire.

We looked forward to this part of each day, but today a shout of, “Hello, the camp!” brought our stragglers hurrying, for visitors to our remote camp were a special treat. It was a fellow miner from upstream on his way out of the canyon to visit family and get supplies. He joined us for awhile. He had been coming to this area since he was a boy, with his father, and still returned for a portion of each summer.

All mining areas are rich in history, and this area was well-documented by a local historian. We often went over portions of his book at our campfires. Signs of the past were plentiful all around us. In the creek, still in place in front of our camp, were two huge logs, the base of a long-ago dam. From that point down, up on the mountainside, remains of a wooden flume, which now provided us with a trail the length of our claim. It was a welcome alternative to the long-hike down the middle of the creek through our narrow canyon, crossing deep pools or scrambling over bedrock and huge boulders.

We continuously dredged-up reminders of former miners-square nails and mule shoes, hand-forged picks and other tools, and even old coins. Dimes from 1839, 1848 and 1849 and a “large” cent from 1832, all caused as much excitement as the gold nuggets we were finding.

We continuously dredged-up reminders of former miners-square nails and mule shoes, hand-forged picks and other tools, and even old coins. Dimes from 1839, 1848 and 1849 and a “large” cent from 1832, all caused as much excitement as the gold nuggets we were finding.

On this evening, our visitor told us a story that intrigued us all. It was of an old mine just over the mountain. It was worked and guarded by an old hermit for many years, who had disappeared about 10 years before, after a shoot-out with law enforcement officers.

Our visitor told of a three-story cabin still standing, and a lot of equipment around; since the only way in or out of the valley was to hike over a mountain. He said he had been shown an old photo of a huge steam engine suspended on a cable as it was being taken across our canyon, 1,000 feet or more in the air. Downstream a short way, he pointed out the spot it had been taken across. According to him, the huge engine was still there.

After he left, we excitedly made plans to hike over the mountain on our next day-off from dredging; and in the meantime, we checked our book for information. It seemed the steam engine was brought in 1901 to power a lumber mill for wood to rebuild and repair our flume. Wow, that flume crossed the mountains for eleven miles to provide water to hydraulic mine a rich area. There were even several photos in the book that were taken long ago.

Our day finally arrived, and we were all up early, packing lunches and donning packs while the air was still crisp and dew sparkled around us on the plants. The sun was just rising over the mountain as we forded our creek and started up the mountain on the other side. It was a steep climb, and we paused often to admire the beautiful patches of wildflowers and pick raspberries.

Our day finally arrived, and we were all up early, packing lunches and donning packs while the air was still crisp and dew sparkled around us on the plants. The sun was just rising over the mountain as we forded our creek and started up the mountain on the other side. It was a steep climb, and we paused often to admire the beautiful patches of wildflowers and pick raspberries.

Soon, a shout from those ahead brought us up the last steep ascent, where we struck the trail our visitor told us of. It went around the top of the mountain at this point. We were shaded by the forest now-much welcomed after our steep climb. We were now on a narrow trail just wide enough for a mule. It was carpeted thickly with pine needles and leaves, and well-worn from many years of use.

When we reached the other side, the mountain was very steep, but the trail had a series of switchbacks which made the descent relatively easy. As we neared the bottom, we saw the first sign indicating that we were in the right place. Here were faint, but unmistakable, remains of the chute used to transport logs from the top of the mountain to the bottom. This was shown in one of the photos in our book.

We didn’t pause for long, because we could hear the creek and knew we were almost there. The trail ended at the creek. We crossed the creek, passing through the trees lining the bank to see if we could pick up the trail, again.

Once through, we stopped in astonishment. Immediately before us rose the rear of a tall narrow cabin. Its weathered boards grew moss, and its smokestack stuck out at a crazy angle. It dominated a large meadow. We saw several other cabins-all in various stages of falling down-and trails branching off in all directions.

This was definitely the scene from our book; but the whole area was denuded of trees in the photo. Except the meadow was now covered in forest, making it difficult to recognize. At that moment, we felt as though we were stepping from a time machine into the past, into a scene frozen in time, undisturbed.

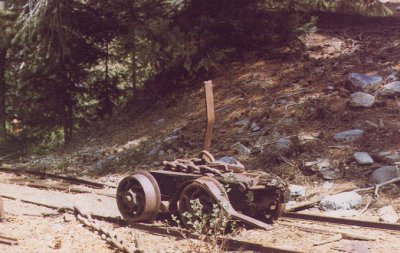

As we circled the cabin and approached the front, we found a crude sluice leaning against a tree and a large old grinding wheel from a blacksmith’s shop, laying broken were it fell from its stand as the wood rotted and could no longer hold it. An old wheelbarrow, ore cars and a narrow gauge track which had come from Germany were all visible.

However, before investigating the rest, we wanted to see what was inside the cabin. The door stood wide open, but we called, “Hello” into the interior several times. Receiving no answer, we finally stepped up inside onto the worn, wooden floor and waited for our eyes to adjust to the gloom.

Once we could see, we found ourselves in the single room which made up the entire ground floor. The room was dominated by an immense, fancy wood cook stove. How we wished that stove could talk, and what stories we imagined it could tell! It had obviously been well cared for; and even with its heavy coating of dust, it retained an air of dignity.

The rest of the room in contrast, had crude, handmade furniture–a large table, benches and stools, and crates and powder boxes tacked to the walls to hold supplies. The only bright color in the room came from old cork-top bottles of amber, blue and green placed on a window ledge to catch the sunlight. A stairway tilted against one wall proved to be pretty sturdy; so we slowly ascended it, one at a time. This room had been a bedroom, and we were once again surprised by what we found. Sunlight, filtering through the dusty window, lay across a narrow iron bedstead covered with an old, worn wool blanket.

As we looked around, sunlight streamed through large cracks between the wall-boards. How cold it must have been when the winter winds and snow came whistling through!

As we looked around, sunlight streamed through large cracks between the wall-boards. How cold it must have been when the winter winds and snow came whistling through!

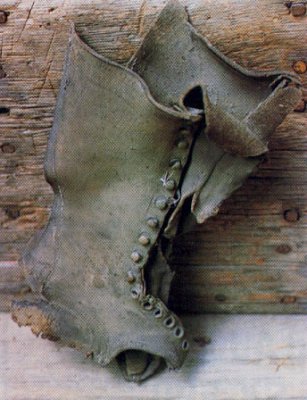

There were two more narrow beds of the same type with only ancient, lumpy ticking mattresses covering the sadly-sagging springs. The end of a peach crate with a once-bright label was propped on a wall ledge, now dull and faded. A coat, looking as if it would disintegrate if touched, was hanging on a nail in the wall next to one of the beds. This room had an air of sadness about it, and we touched nothing. Soon, we filed back down the tilted stairway and went out into the sunlight.

We spent the rest of the day exploring the area. We found one path that led past a whole row of small cabins, each one collapsed, with many square nails laying about, with the doors and windows laying where they’d fallen. The trees were very thick here, many grew inside the cabin walls.

Following a narrow gauge track, it was found to end at the entrance to a tunnel which was completely filled in with dirt and boulders. There were several ore cars about the area.

Harder to find was the steam engine, but it was found just where it had been in the photograph, and a search through the thick trees and underbrush disclosed its building collapsed around it. We found signs of other buildings, some of which had burned, others we knew not what had happened. It was definitely a bustling little community at one time. We also found some signs of more recent inhabitants of the area, but no signs of any trash at all. They, too, seemed to have left everything undisturbed. They also must have felt that this was a very special place.

All too soon, it grew late and we had to cross back over the mountain and return home. We vowed we would return, but we only had two weeks left on the claim and we did not make it back. However, we planned to make the journey again the next summer.

All too soon, it grew late and we had to cross back over the mountain and return home. We vowed we would return, but we only had two weeks left on the claim and we did not make it back. However, we planned to make the journey again the next summer.

When we returned that next summer, we had a visit from the couple who bought the claim. It was then that we discovered it had been destroyed by fire just one month after our visit. It was speculated that a hunter took refuge there during a snow-storm, and lit the old stove, then fell asleep. He burned in the fire also. We were saddened by the loss of life and of the cabin. It was a special piece of history that can never be replaced.

Although we took nothing with us but photographs, nothing was needed. We had our memories of it, and always will. It gave us a special feeling to leave it as we found it, and the fact that it burned did nothing to diminish that feeling.

We feel very privileged and special to have had our chance to step back in time and gain a special closeness and insight into what it must have been like to live there so long ago. We feel our children, especially, had an experience that few of their generation will ever have.

I didn’t ever go back, and don’t intend to. As long as I don’t, the cabin still stands there, waiting.

- Here is where you can buy a sample of natural gold.

- Here is where you can buy a basic gold prospecting kit.

- More About Gold Prospecting

- More Gold Mining Adventures

- More History on Gold Mining

- Schedule of Events

- Best-selling Books & DVD’s on this Subject