BY PHIL PHILCOX

Within 100 miles as the crow flies, California offers both the highest pint in the lower 48 states –Mount Whitney at 14,449 — and the lowest spot on the continent — Badwater at Death Valley Monument Park at 282 feet below sea level. From its northern borders to its southern coastline, there are majestic mountains, rugged deserts, vibrant cosmopolitan cities, and virtually every diversion a vacationer needs. Its varied climate finds swimmers splashing in the Pacific Ocean in January while skiers slalom down snow-covered slopes only a few hundred miles away. Outdoor lovers can head for trails, camp- grounds and forests in the High Sierra while surfers and sunbathers will find long stretches of sandy beaches along the coast. The warm Mojave and Colorado deserts are a haven for those seeking relief from freezing weather elsewhere in the United States. With over a hundred cities each with populations of over 50,000 and the six largest cities boasting of populations between 200,000 and over two million, the cultural experiences are as varied as the outdoor experiences. The California Office of Tourism offers a variety of free vacationing material, including motoring guides and road maps, directories of hotels and campgrounds covering both the entire state and specific areas and booklets and brochures pointing out the key vacationing spots and what they have to offer; Write them at 1030 -13th St., Sacramento, CA 95814 (916-322-1396).

Twenty-Six Driving Tours is an interesting free 54-page book that lists the most scenic routes around the state with maps and information on sightsee- ing each area. This free book, combined with the directories of campgrounds, will provide all you need to decide where to go, how to get there and where to stay upon arrival.

The California State Park System consists of 270 parks, beaches, reserves and recreational areas. A guide to state parks is available for $2 from the Information Office of Department of State Parks, Box 2390, Sacramento CA 95811 (916-445-6477).

The Bureau of Land Management maintains 35 campgrounds around the state and they are listed, along with facilities, in two free booklets, Camping in California and Camping On Public Lands, available from the Bureau of Land Management, 2135 Butano Dr., Sacramento, CA 95825.

A guide to over 200 private camp- grounds is available for $2 from the California Travel Parks Association Information Service, 371 Idylwild Court, Redwood City, CA 94061, (415- 365-1144).

With over 5,000 lakes, 30,000 miles of streams and rivers and 1,200 miles of coastline, there’s ample opportunity to get involved in water sports while vacationing in the state. California’s northern coast is known for its rugged shores where the foothills of nearby mountains drop down to meet the pounding surf. In central California, rivers running through Gold Country merge in Sacramento, providing excellent boating, swimming and fishing conditions.

In all vacationing areas, the camping conditions are excellent, honed over years. Information on searching for gold on the Klamath River in the north state can be obtained from The New 49’ers, (530) 493-2012; house boating-afloat on Shasta Lake north of Redding, and rental sources can be obtained from the Shasta- Cascade Wonderland Association, Box 1900, Redding, CA 96001 (530-243- 2643).

California’s southern region has a sunny, Mediterranean climate with broad beaches and bustling cities offering a variety of attractions. San Diego offers swimming at local beaches, surfing and skin diving in summer and access to major attractions–Sea World, the San Diego Zoo, Balboa Park and the Wild Animal Park. Whale-watching is popular in winter, from charter boats or lookout points.

Moving inland, the starkness of the desert is in marked contrast to the rest of the state. Consisting mainly of Death Valley and the Mojave Desert, it’s prettiest here during late fall when temperatures are pleasant and the ground’s alive with desert plants. In the heart of the desert lies the splendor of Palm Springs.

Orange County is the home of Disneyland, Knott’s Berry Farm and Lion Country Safari. Newport, Huntington and Laguna beaches are popular areas where daily cruises visit nearby Catalina Island.

Los Angeles proudly flaunts its heritage on Olvera Street–vendors sell Mexican handcrafts while people dance in the streets to Mariachi bands. Nearby Hollywood has tours of movie studios. Several good beaches are within an hour’s drive of downtown LA, including Santa Monica, with its carnival rides and boardwalk.

San Francisco is rich in the history of the Gold Rush Days when the town was a boisterous frontier port, and gateway to gold country.

The Lake Tahoe region is a year- round resort area, with camping and water activities during summer; ski and winter sports after November. Set amid towering peaks, Squaw Valley was the site of the 1960 Winter Olympics.

This year’s (1998’s) 150th Anniversary of California’s Gold Rush has sparked many special celebrations in the Mother Lode area all during summer months, culminating in the World Gold panning Championships, to be held at Marshall Gold Discovery State Historic Park, PO Box 265 (310 Back St.) Coloma, CA 95613 (530-622-3470). Teams and individuals from many other countries will be participating, and Governor Wilson has declared a celebration that will feature a great time for all visitors. If you haven’t made your plans to participate yet, now’s the time to do so!

- Here is where you can buy a sample of natural gold.

- Here is where you can buy a basic gold prospecting kit.

- More gold mining adventures

- More about how to prospect for gold

- Schedule of upcoming events

- Books and Videos by Dave McCracken.

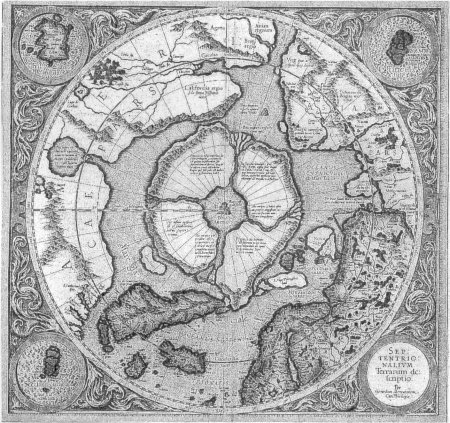

“Chart of the North Pole,

“Chart of the North Pole,

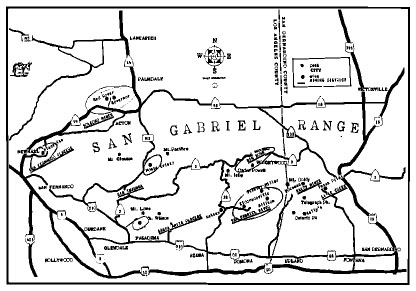

The Legendary Monte Cristo find in Placerita Canyon was not the first discovery of gold in California, either. It was simply the first documented claim. Rumors of gold circulated as far back as the late 1700’s. One legend surrounds the Lost Padres Mine, which was supposed to have been connected with Mission San Fernando. Vast amounts of gold were said to exist at Mill Creek.

The Legendary Monte Cristo find in Placerita Canyon was not the first discovery of gold in California, either. It was simply the first documented claim. Rumors of gold circulated as far back as the late 1700’s. One legend surrounds the Lost Padres Mine, which was supposed to have been connected with Mission San Fernando. Vast amounts of gold were said to exist at Mill Creek. Early in the 1850’s, Englishman John Titus came to the wild Klamath River area to mine for gold. He staked a mining claim along a small creek which would later bear his name. Titus Creek flowed down a long and high ridge southeast of

Early in the 1850’s, Englishman John Titus came to the wild Klamath River area to mine for gold. He staked a mining claim along a small creek which would later bear his name. Titus Creek flowed down a long and high ridge southeast of

This mine is located in geologic strata and soils closely related to those of Indian Town. Gold and gravel traveled downstream from Classic Hill to Indian Town over many millennia. Elevations in this area range from 1,800 feet at the foot of the Classic Hill, up to 7,310 feet at Preston Peak, “Master of the Coast Range.” The Siskiyou Mountain Range runs east and west, connecting the Cascade Range to the California Coast Range. Little Grayback Mountain connects to the west and Soda Mountain connects to the east.

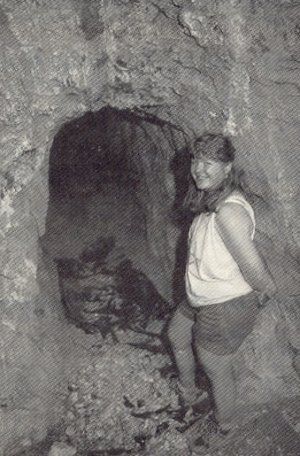

This mine is located in geologic strata and soils closely related to those of Indian Town. Gold and gravel traveled downstream from Classic Hill to Indian Town over many millennia. Elevations in this area range from 1,800 feet at the foot of the Classic Hill, up to 7,310 feet at Preston Peak, “Master of the Coast Range.” The Siskiyou Mountain Range runs east and west, connecting the Cascade Range to the California Coast Range. Little Grayback Mountain connects to the west and Soda Mountain connects to the east. Here is where John Titus and Jim Camp found truly large amounts of gold. Today, you can walk the mine (it’s privately owned; so you must get the owner’s permission to prospect it) and see gravelly, loam soils varying in color from brown to pink. You can still see outcrops of fractured metamorphic rock. Most important, you can find pockets of river-washed gravels that have been collected in holes and depressions of the terrain over millions of years. Many of these gravel traps collected gold along with the gravel.

Here is where John Titus and Jim Camp found truly large amounts of gold. Today, you can walk the mine (it’s privately owned; so you must get the owner’s permission to prospect it) and see gravelly, loam soils varying in color from brown to pink. You can still see outcrops of fractured metamorphic rock. Most important, you can find pockets of river-washed gravels that have been collected in holes and depressions of the terrain over millions of years. Many of these gravel traps collected gold along with the gravel. In the 1880’s Jacksonville was one of the largest and most well known gold boom-towns in the west.

In the 1880’s Jacksonville was one of the largest and most well known gold boom-towns in the west. This “Waldo Pack Trail” is the same one that was used to deliver beef cattle and hogs from the Bybee Ranch and others in the Rogue and Applegate Valleys. Cowboys would meet the miners at Big Meadows to exchange gold for food and animals. This same trail, winding through Siskiyou Mountain timber, was also used to deliver gold from Happy Camp and Indian Town to gold buyers in Oregon.

This “Waldo Pack Trail” is the same one that was used to deliver beef cattle and hogs from the Bybee Ranch and others in the Rogue and Applegate Valleys. Cowboys would meet the miners at Big Meadows to exchange gold for food and animals. This same trail, winding through Siskiyou Mountain timber, was also used to deliver gold from Happy Camp and Indian Town to gold buyers in Oregon.

make the half-hour trip to church for Sunday services. I begged Mama to let me stay home from church because I had something I wished to do. It took a lot of pleading, and she finally agreed to let me stay home, but only if my brother and sister stayed and I would agree to watch after them. What I had planned was an exciting day of bow and arrow fishing in the creek down behind the house. This was one of my favorite pastimes, and with all the chores around the farm, Sunday’s were the only free time I had.

make the half-hour trip to church for Sunday services. I begged Mama to let me stay home from church because I had something I wished to do. It took a lot of pleading, and she finally agreed to let me stay home, but only if my brother and sister stayed and I would agree to watch after them. What I had planned was an exciting day of bow and arrow fishing in the creek down behind the house. This was one of my favorite pastimes, and with all the chores around the farm, Sunday’s were the only free time I had.

area and nearby counties began searching their own creeks and streams for gold. Many were rewarded handsomely for their search and many new discoveries were made. At this time, no one knew exactly where the gold came from; all that was known was it could be found on the creek bottoms and along the edges of the creeks. This type of mining was called placer mining, and for many years was the only type of mining to be done.

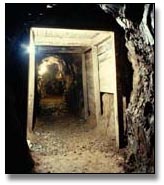

area and nearby counties began searching their own creeks and streams for gold. Many were rewarded handsomely for their search and many new discoveries were made. At this time, no one knew exactly where the gold came from; all that was known was it could be found on the creek bottoms and along the edges of the creeks. This type of mining was called placer mining, and for many years was the only type of mining to be done. In 1971, the State of North Carolina purchased the Reed property. It is now a state historical site. The State constructed a large museum which houses many relics and mining equipment from the Reed and other mines in the surrounding area. As one enters the museum, it seems as though one has traveled back into time to the days when gold mining was a big business in North Carolina. At the beginning, one will be shown a thirty minute film with actors playing out the discovery of gold at the Reed Mine, and the events of gold mining in the area. After a walk through the museum, seeing actual gold nuggets and gold ore found at the Reed Mine and other mines in the surrounding area, and looking over the type of equipment used in the early days of mining, one will be taken on a guided tour through the old tunnels andworkings of the mine. On these trails, one will see many more diggings and much of the old equipment used at the mine in those days. There is no cost to visit the Reed mine and for anyone visiting North Carolina and wanting to learn more about the history of gold mining in this state I highly recommend visiting the Reed Gold Mine.

In 1971, the State of North Carolina purchased the Reed property. It is now a state historical site. The State constructed a large museum which houses many relics and mining equipment from the Reed and other mines in the surrounding area. As one enters the museum, it seems as though one has traveled back into time to the days when gold mining was a big business in North Carolina. At the beginning, one will be shown a thirty minute film with actors playing out the discovery of gold at the Reed Mine, and the events of gold mining in the area. After a walk through the museum, seeing actual gold nuggets and gold ore found at the Reed Mine and other mines in the surrounding area, and looking over the type of equipment used in the early days of mining, one will be taken on a guided tour through the old tunnels andworkings of the mine. On these trails, one will see many more diggings and much of the old equipment used at the mine in those days. There is no cost to visit the Reed mine and for anyone visiting North Carolina and wanting to learn more about the history of gold mining in this state I highly recommend visiting the Reed Gold Mine.