By Dave McCracken

“Dredging for Diamonds and Gold During the Rainy Season…”

Author’s note: This story is dedicated to Alan Norton (“Alley”), the lead underwater mining specialist who participated in this project. Under near-impossible conditions, Alan made half of the key dives which enabled us to make this a very successful venture.

Author’s note: This story is dedicated to Alan Norton (“Alley”), the lead underwater mining specialist who participated in this project. Under near-impossible conditions, Alan made half of the key dives which enabled us to make this a very successful venture.

There are very few people I know, if any, with more courage, dedication and enthusiasm to successfully complete a difficult mission, than Alan.

If I can make it go right, I try and go overseas at least once or twice a year, usually during our winter months in California, to participate in some kind of a gold mining or treasure hunting adventure. Sometimes I am paid as a consultant to do preliminary evaluations for other companies. Sometimes I just go on my own. Doing these projects in remote and exotic locations is kind of like going back into time, or like going into a different universe. It is always a great adventure! Sometimes, on these different projects, everything goes smooth and easy. Sometimes we uncover fantastic riches. Sometimes we find nothing at all of great value. And, once in awhile, conditions are extraordinarily terrible and put all of our capability and courage to the final test. Such was the case on our recent testing project into the deep, dangerous jungles of southern Venezuela.

Venezuela lies on the north coast of South America along the Caribbean Sea. It is a South American country that ranks as one of the world’s leading producers and exporters of petroleum. Before its petroleum industry began to boom during the 1920’s, Venezuela was one of the poorer countries in South America. The economy was based on agricultural products, such as cocoa and coffee. Since the 1920’s, however, Venezuela has become one of the wealthiest and most rapidly changing countries on the continent. Income from petroleum exports has enabled Venezuela to carry out huge industrial development and modernization programs.

Columbus was the first European explorer to reach Venezuela. In 1498, Columbus landed on the Paria Peninsula. In 1498 and 1499, the Spanish explored most of the Caribbean coast of South America, and Spanish settlers were soon to follow the explorers.*

Almost all Venezuelans speak Spanish, the country’s official language. Indians in remote areas speak various tribal languages.*

I personally was contacted by an American investment group that was in partnership with a Venezuelan mining company. They hired me to spend around thirty days doing a preliminary testing evaluation on a concession (mining property) the company owns in the deep jungles of southern Venezuela. The property was reported to contain volume-amounts of gold and gem-quality diamonds. A river flows across the concession for approximately twenty-five miles.

The company had purchased a 6-inch dredge along with the support equipment. They wanted me to complete a dredge sampling program to see what kind of recovery we could obtain from the river. I brought one other experienced dredger along by the name of Alan Norton. Alan and I had spent several seasons dredging together on the Klamath River in northern California, and I had learned years ago to always bring at least one very capable teammate along when doing diving operations in the jungle environment. This proved to be a really wise decision!

We flew into Caracas, which is the capital of Venezuela, a very nice, modern city with big office buildings and hotels creating a beautiful skyline. Caracas enjoys the reputation of having one of the best night-lives in the world. Poverty is also visible along the outskirts of the city where thousands of people live in small shacks called Ranchos.

The company put us up in the Caracas Hilton where we spent a comfortable night, only to fly out the following morning to Ciudad Bolivar–which is a fairly large city, and the diamond capital of Venezuela.

Upon arriving in Ciudad Bolivar, we were promptly met by representatives of the company, along with the company’s bush boss, an American adventurer by the name of Sam Speerstra. Sam would make a good match for Indiana Jones. It was quickly apparent that he loved danger by the way he drove us through traffic to the small landing strip that we were to shortly depart from on our way to the concession. Sam had us unpack our bags while he arranged to have the aircraft pushed out onto the runway by a half dozen or so airport workers.

The dual engine aircraft was not in the best state of repair. The engine shrouds were held on with bailing wire, some of the cargo doors were held together with duct tape, and the instrument panel was held in place with safety pins, some which were not holding very well.

The dual engine aircraft was not in the best state of repair. The engine shrouds were held on with bailing wire, some of the cargo doors were held together with duct tape, and the instrument panel was held in place with safety pins, some which were not holding very well.

Sam enjoyed my apprehensive observations of the plane while our baggage was being loaded. Proudly, he told me the aircraft company we were using had the best record of non-accidents in the whole country. However, he also said the landing strip on the concession was quite small and hard to get into because of a large hill that had to be dropped over quickly in order to touch down at the beginning of the runway. In fact, he informed me the company had lost one of its planes trying to land on the concession during the week before. I asked if anyone was hurt. “All dead,” Sam responded, with a smile on his face. And he was serious! .

While, for proprietary reasons, I am not able to divulge the exact location where we were operating, I can say that we were at least several hundred miles into the jungle south of Ciudad Bolivar, towards the Brazilian border.

In this instance, we were asked to do this preliminary evaluation just as the rainy season was getting started. Shortly after taking off in the dual engine plane, we began seeing large rolling clouds. The further south we flew; the larger and more dense the clouds became.

About halfway to our destination, the pilot put down on a small landing strip in a relatively small village to pick up a full load of mining equipment which he had to leave there the day before. He had not been able to get out to the concession because of the almost zero visibility caused by the heavy rains and clouds. As we landed on this strip, the first thing we noticed was a completely wrecked plane that had crashed there. This added to our apprehension and to Sam’s sense of adventure.

It took about an hour to pack the airplane completely full of mining equipment. Since we had to remove the seats to make room for gear, Alley and I were directed to lay up on top of the gear that was stacked up in the belly of the plane. No seat belts! And the plane was loaded so heavily, even the pilot was not sure whether or not we were going to make it off the runway when we took off. We barely made it, and the plane was very sluggish to fly for the remainder of that trip.

It took about an hour to pack the airplane completely full of mining equipment. Since we had to remove the seats to make room for gear, Alley and I were directed to lay up on top of the gear that was stacked up in the belly of the plane. No seat belts! And the plane was loaded so heavily, even the pilot was not sure whether or not we were going to make it off the runway when we took off. We barely made it, and the plane was very sluggish to fly for the remainder of that trip.

We were in and out of clouds for the remainder of the flight, much of the time with zero visibility outside of the airplane. Occasionally, we would break through the clouds and see nothing but dense jungle below us as far as the eye could see in any direction. This was the Amazon! Sam took the time to educate us on the many different types of animals and insects which would certainly devour us if we were to have the bad fortune of crashing. Tigers and jaguars, driven out of some areas by villagers, only to be more hungry and ferocious in other areas. Six-foot long electric eels, called Trembladores by the natives, capable of electrocuting a man with 440 volts, and man-eating piranha were all through the rivers and streams, according to Sam. He told us of bushmaster snakes, the most dreaded vipers in all of South America. Sam said he personally had seen them up to twelve feet in length with a head about the size of a football. “Very aggressive–they have been known to chase a man down.” Sam said you could see the venom squirting out of the fangs even as the snake started to make a strike– one of the most horrifying experiences he had ever seen. “But, not to worry, I brought along a shotgun just in case we get in trouble,” Sam told us as hundreds of miles of jungle passed beneath us.

After quite some time, at a point when the clouds cleared away just long enough to see, Sam pointed down to a short runway cut out of the jungle. At first, we could not believe we truly were going to try and land there. Sure enough, it was the base camp for the concession. We made one low pass over it. The base camp looked large and well equipped. There was also a small local village right near the base camp. The landing strip was filled with puddles and looked to be mostly mud. Alley and I were a little nervous after Sam’s big buildup, and we had very good reason to be nervous.

After quite some time, at a point when the clouds cleared away just long enough to see, Sam pointed down to a short runway cut out of the jungle. At first, we could not believe we truly were going to try and land there. Sure enough, it was the base camp for the concession. We made one low pass over it. The base camp looked large and well equipped. There was also a small local village right near the base camp. The landing strip was filled with puddles and looked to be mostly mud. Alley and I were a little nervous after Sam’s big buildup, and we had very good reason to be nervous.

In order to land on the strip properly, the pilot had to fly just over the treetops, around a ridge, to drop quickly over a hill almost into a dive to get low enough, fast enough, to meet the beginning of the runway. The pilot’s skill was very good, although it is the only time in my life I have ever been in a plane that actually tapped the tops of trees as it was going in for a landing. The thump, thump of the trees hitting the wheels of the plane put me in somewhat of a panic. But it was all for nothing, because within seconds we were safely down on the runway. The pilot and Sam seemed to think nothing of the hair-raising landing experience. Alley and I felt like cheering that we were still alive. This was the mental state we were in when we arrived in the jungle. And it was just the beginning!

Local villagers came out to help us unload the plane. They all seemed like very nice people. After having a chance to load our gear into the bungalow, Sam gave us a short tour of the base camp. The whole area was fenced in. There were numerous screened-in bungalows for the various crew member sleeping quarters, a large kitchen, an office, and a large screened-in workshop area. The company had spent a lot of money getting it all set up. There was a jeep and two off-road motorcycles—all in a poor state of repair. They operated, but without any brakes.

Local villagers came out to help us unload the plane. They all seemed like very nice people. After having a chance to load our gear into the bungalow, Sam gave us a short tour of the base camp. The whole area was fenced in. There were numerous screened-in bungalows for the various crew member sleeping quarters, a large kitchen, an office, and a large screened-in workshop area. The company had spent a lot of money getting it all set up. There was a jeep and two off-road motorcycles—all in a poor state of repair. They operated, but without any brakes.

After we had a chance to relax a bit, Sam insisted we go meet the “Capitan,” who was the chief of the local village. We had to arrange for several boats and a small group of local Indians to support our operation along the river. Sam explained to us that public relations were very important and that we must go over and have a friendly drink with the Capitan. We assumed Sam was bringing the Capitan a bottle of Scotch or Brandy or something as a gift. But that’s not the way it happened. Sam preferred to drink the local mild alcoholic beverage called Cochili. This drink is made by the local Indians from squeezing the juice out of a special plant that they grow. The juice is allowed to ferment in the open air for several days or weeks, depending upon the weather. It is a milky white-like substance with clumps of bread-like soggy goo (kind of like pollywog eggs), along with some greenish-brown mold mixed in–it was great to behold! It smelled almost as bad as it looked.

We met the chief, who looked totally wasted on something–probably the Cochili drink. And immediately upon our arrival, the chief ordered some children to bring glasses and drink for everyone. Promptly, our glasses were filled to the rims. Sam quickly downed his first glass, licked his lips, smiled and said, “This is all in the name of good local public relations!” To be polite, I downed half my glass and did my best to choke back my gag. The stuff tasted terrible! I realized my mistake right away when one of the kids immediately took my glass and refilled it to the brim. Alley was paying close attention and slowly sipped his drink, and I followed suit. There was no place to spit if out without being seen, so we had to drink it down. Sam put down three or four more glasses and shortly was slurring his Spanish in final negotiations with the chief. I’m not really sure they understood each other concerning any of the details, but everyone seemed happy with the negotiation.

We met the chief, who looked totally wasted on something–probably the Cochili drink. And immediately upon our arrival, the chief ordered some children to bring glasses and drink for everyone. Promptly, our glasses were filled to the rims. Sam quickly downed his first glass, licked his lips, smiled and said, “This is all in the name of good local public relations!” To be polite, I downed half my glass and did my best to choke back my gag. The stuff tasted terrible! I realized my mistake right away when one of the kids immediately took my glass and refilled it to the brim. Alley was paying close attention and slowly sipped his drink, and I followed suit. There was no place to spit if out without being seen, so we had to drink it down. Sam put down three or four more glasses and shortly was slurring his Spanish in final negotiations with the chief. I’m not really sure they understood each other concerning any of the details, but everyone seemed happy with the negotiation.

It was a good thing that the rainy season prevented the remainder of our mining equipment to arrive in the jungle for the next two days. Because I spent the next few days with a severe case of the jungle blues. I was popping Lomotil tablets left and right to try and dry up my system and finally started making progress on the third day in the jungle. Man was I sick!

Alan boasted that he never had a case of diarrhea in his life and that he never would. Sam spent several hours every evening drinking Cochili with the local Indians who would accompany us into the jungle. He was getting to know them better.

The weather was hot and muggy, although the heavy rains had not started yet in earnest. The jungle was alive, especially at night when the jungle noises were almost deafening. It was certainly not a nice place to go for a friendly, evening hike. We were glad for the fence that surrounded the compound.

On the third day, still weak from the fever, but feeling like I should be productive at something, I decided to take a motorcycle ride on the new jeep trail which had recently been hand-cut several miles to the river. Why is it that I always know when I am going to come upon a nasty snake just an instant before I see it? As I rounded the first corner on the trail, a large viper took off ahead of me up the trail faster than a man could run. No brakes! Finally, I stopped the bike, turned around, and returned to camp to rest up some more.

“Once the rains started, the water was so muddy we had zero visibility underwater and had to find our way through the broken branches of submerged trees by feel”

The remainder of our gear finally arrived on the following day. We assembled everything to make sure it was all there. It wasn’t. We were missing the assembly bolts for the six-inch dredge; we had only one weight belt; and we had no air reserve tank for the hookah system! This was not good!

We finally ended up using bailing wire to hold the dredge together, and had to settle for hooking the airline directly to the dredge’s air compressor. One weight belt was all we were going to get—not much margin for error! The entire operation would depend upon us not losing that single weight belt.

On the following day, all the equipment was packed to the river by the local villagers. This was not an easy two-mile pack, because the trail was very muddy and was quite steep up and down the whole distance. Alan and I were using one of the motorcycles to get up and down the trail, which was a real adventure with no brakes.

One very interesting thing about this jungle is that huge trees, for no apparent reason at all, come crashing down. At least several times a day, we would hear huge trees crashing down in a deafening roar. On one occasion, Alan and I were returning to base camp on the jeep trail. We had just come up that trail fifteen minutes before. As we were going down a muddy hill and rounding a bend, we ran smack right into a huge tree which had just fallen across the trail. Good thing I was driving! We smashed into the tree with both of us flying off the bike. Luckily, neither of us were hurt more than just a few bumps and bruises, although the front-end of the motorcycle was damaged. Chalk up one more for the jungle.

One very interesting thing about this jungle is that huge trees, for no apparent reason at all, come crashing down. At least several times a day, we would hear huge trees crashing down in a deafening roar. On one occasion, Alan and I were returning to base camp on the jeep trail. We had just come up that trail fifteen minutes before. As we were going down a muddy hill and rounding a bend, we ran smack right into a huge tree which had just fallen across the trail. Good thing I was driving! We smashed into the tree with both of us flying off the bike. Luckily, neither of us were hurt more than just a few bumps and bruises, although the front-end of the motorcycle was damaged. Chalk up one more for the jungle.

During the time while equipment was being transferred to the river and set up, we took several airplane rides to survey the section of river which we were planning to sample, and to make arrangements at a small village (with a landing strip) about twenty-five miles downstream to obtain fuel and some basic supplies as needed during our sampling trip. Once we started, we would not be in contact with the base camp until our sampling project was complete–which was to be about twenty-five to thirty days later. In flying around the area and landing on the two strips, it soon became apparent that the pilot was very skilled. While he definitely was flying by the seat of his pants, the conditions were normal and it was no big thing (to him). Sam just had the advantage of prior experiences at the concession and was psyching us out–all in fun. It only took a little while to catch onto his game.

One of the things we quickly learned in the South American jungle, is that you never stand still for more than just a few seconds. Otherwise, a steady line of ants, mites, and other meat-eating critters will crawl up your legs, inside or outside your pants, and go to work on you. We had plenty of mite bites–which hurt, itch, and generally drive you crazy for about five or six days before they start healing. And, we learned to never brush up against bushes as long as we could help it, for fear of getting fire ants all over us. They sting like crazy!

We never allowed our bare skin (especially bare feet) to come in contact with the bare ground in or around the camps. This is because of chiggers. Ants were everywhere. Whole armies of big ants could be seen to follow a single file line up and down the trail for a mile or more, carrying torn up leaves from a tree which was actively being stripped clean by other ants. The whole jungle was crawling with life. Every square inch had some creature that was starving to take a good bite out of us. Perhaps it was the muggy weather, or maybe weakness from the jungle fever, but my first impression of the South American jungle was that it was doing everything it could to suck the life energy out of my body.

On more than one occasion, some huge animal would go crashing through the jungle just a short distance from where we were standing. We never saw the animals, but had the continuous feeling that some huge cat or wild boar was ready to come smashing in on us. And, of course, the shotgun was never in my own hands when this occurred, which was probably a good thing for everyone else in the vicinity.

“We allowed the natives to swim in the river first to make sure there were not going to be problems with piranha and Trembladores”

While we were packing gear, one of the village-helpers came running in to show off a bird spider he had caught and skewered on the end of his machete. This spider was bigger than my hand; it looked like a huge tarantula. According to the natives, these fearsome spiders catch birds to feed on, not flies, in their webs.

Our first few days on the river were absolutely, breathtakingly, exotically beautiful. The sun came out. The river was low and semi-clear. The water was warm, but just cool enough to give us satisfaction from the muggy air temperatures. We did not need wetsuits other than to protect our bodies from scrapes and bruises. We dredged a half dozen or so easy sample holes. Gravel was shallow to bedrock. The first camp was quite comfortable. The Indians were using their bows and extra long arrows to catch great-tasting fish. Everything was perfect. I remember wondering why I had such a problem adapting to the jungle in the first place. It was like paradise on the river, and we were even getting paid to be there!

We allowed the natives to swim in the river first, to make sure there were not going to be problems with piranha and Trembladores. This is not a bad thing to do. We did not make them swim first. They simply dove in. We always watch for this in a jungle environment. The local Indians know what it is safe to do. After watching the Indians swim for quite some time, we decided it was safe.

The natives live under grass roof shelters–often with no sides. They hang hammocks from the supporting roof beams and sleep at least several feet off the ground. Since Ally and I don’t sleep very well in hammocks, we brought along cots, instead. On our first night in the jungle, Sam insisted the cots would be just fine on the ground. They had short legs which put the cots about six inches off the ground. Alan and I both had sleeping bags which could be zipped up. Sam simply had one dirty white sheet. About midway through the night, Sam’s cot collapsed on him. Shortly thereafter, he was dancing around the camp yelling, “Fleas!” He was barefooted, and the natives spent the next two weeks picking chigger eggs out of the bottom of his feet with sharp pointed sticks.

Let me explain chigger eggs: These critters somehow lay eggs inside the pores of your skin. The eggs grow larger and larger, causing an open sore. It keeps getting worse until you realize it is not just a mite bite. The egg has to be removed with a sharp piece of wood, kind of like a toothpick. The eggs I saw were about the size of a soft, white BB when removed. It was explained that this was really a sack full of eggs. The trick was to get rid of them before the sack broke. Otherwise, the problem was severely compounded. Apparently, the dogs carried these chiggers all over themselves. We were instructed to not pat the dogs for this reason. It was a good lesson for us, and we learned it quickly from Sam’s experience.

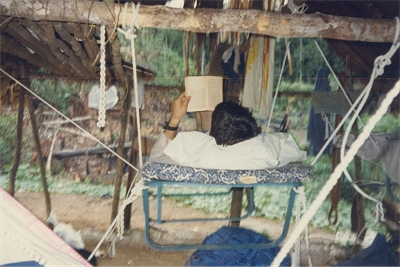

We had a three hundred-foot roll of half-inch nylon rope with us for the mining operation. The following day, Alley and I allocated one hundred and fifty feet of that rope to be used to tie our cots up into the shelter beams to keep us well away from the ground. Our Indian guides were quite amused by this. The rest of the rope was used in the dredging operation.

We had a three hundred-foot roll of half-inch nylon rope with us for the mining operation. The following day, Alley and I allocated one hundred and fifty feet of that rope to be used to tie our cots up into the shelter beams to keep us well away from the ground. Our Indian guides were quite amused by this. The rest of the rope was used in the dredging operation.

On about the fourth day on the river, Sam returned to the base camp to supervise the other surface digging testing operations. Our cook became extremely angry soon after Sam left. I later found out that he was contracted by Sam to spend only five days in the jungle. Sam left without taking him along. He was stuck with us in the jungle for the next twenty days or so, and we all paid for his anger in the food he prepared for us. We would get fresh-made pan-fried bread every morning that was so saturated with oil that you could squeeze the oil out of it in your hand. This, along with a can of sardines for breakfast. We got leftover bread from breakfast for lunch, along with more sardines. We also got sardines with stale bread for dinner. The cook was basically on strike. Luckily, there were plenty of banana and mango trees along the river to supplement our diet.

“It was easy to follow the tributary because it was running straight black mud”

But we had our attention on other matters. The heavy rains began on the day Sam departed. In one night, the river rose up at least fifteen feet. And it roared! Entire trees were washing downriver. It was a torrent. The water was the color of brown mud. The river rose up and spread out into the jungle, making the whole area into a huge, forested lake. There were no riverbanks to be found in most areas. Our own camp was within four feet of being washed away. We knew where the river was only because of the swift moving water. Some of the river was difficult to travel upon, because it was flowing through the treetop canopy, which was occupied here and there by huge nests of African killer bees and other hornets and varmints. It was a nightmare!

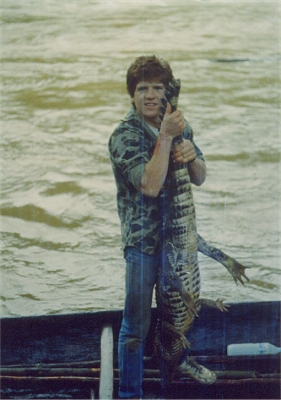

On top of that, the natives caught a hundred-pound Cayman (alligator) with a net out of one of our dredge holes where they had been fishing. It was certainly big enough to take a man’s arm off. At that point, the natives told us these animals came much larger on the river.

On top of that, the natives caught a hundred-pound Cayman (alligator) with a net out of one of our dredge holes where they had been fishing. It was certainly big enough to take a man’s arm off. At that point, the natives told us these animals came much larger on the river.

That was the day Alley decided to come down with his own bout of jungle fever.

Since Alley was incapacitated, I chose that day to hike back to the base camp and have a talk with Sam about the adverse diving conditions. Although we had recovered some diamonds and gold already, I was not comfortable with the recovery system for diamond recovery. I also was not excited about diving in the swollen, muddy river. I would like to get a look at what is going to eat me before I die! Even the natives, who were standing in line to dive in the clear water, absolutely refused to dive in the river once the rains started. This was definitely a very bad sign. Sam managed to get the big boss on the radio and I explained the problems to him. In turn, he told me that his entire company was depending upon the results of my sampling project to justify further investment in the project once the rainy season tapered off. “It all depends on you, Dave.” I told him we would do the best that we could.

The next day, Alan was so weak from diarrhea, that he was barely able to get out of his cot to do his duty outside of camp. I felt my own duty was to go do some sampling with the help of two natives as my tenders. Rather than dredge on the main river (which was raging), I decided to test one of the main tributaries which had the reputation of having lots of diamonds. The natives left me to keep an eye on the dredge, which was tied to the canopy of some trees at the mouth of this tributary, while they hacked a trail through the tree branches several hundred yards up this creek–which was now an endless lake out into the jungle. It took several hours for them to make the trail with their machetes. It was easy to follow the tributary because it was flowing straight, black mud, compared to the brown color of the river water.

While I was standing on the dredge waiting for the natives to finish the trail, a huge bee buzzed by my head. Within a couple minutes, there were about a dozen of these bees buzzing me. They were really mean! I had my hat off and was flailing around wildly trying to keep them away. There was no place I could go off to, to get away from them. Finally, I had to jump into the water and hide underneath the sluice box. This is where the natives found me when they returned. They were quite amused.

It took quite some time for us to drag the dredge up this tributary, because the branches were just hacked off at water level. I was looking for a place we could work off of a streambank, but eventually gave up on that idea. The water was simply too deep. I ended up throwing the suction hose over the side of the dredge, primed and started the pump, put on my seventy-pound lead weight belt and other diving gear, crawled over the side and shimmied carefully down the thirty-foot suction hose. The problem was feeling my way down through the submerged tree limbs to find bottom. There were logs and branches everywhere. I was in total darkness–complete zero visibility. Everything was done by feel, sensation and yes, fear. I finally found the bottom and estimated it to be about twenty-five feet deep by the amount of suction hose I had remaining with me on the bottom. It was scary down there!

After seeing the Cayman on the day before, I had visions of being grabbed by a huge alligator, and other visions of being grabbed by a huge python. A strong voice from inside my heart was telling me to end the dive. It was too darn dangerous! Any emergency would have me and my airline all tangled in the branches. Having to dump the weight belt would put an end to the entire program, because we only had one weight belt.

I decided that I should complete the sample after all we had gone through to get me on the bottom. This is what I was being paid to do.

As I dredged into the gravels on the bottom, by feel, I discovered more buried branches and logs. These, I simply tossed behind me just like I do with oversized rocks. I got into a pretty steady routine down there and was making good progress. But the strong picture of huge alligators and pythons was right there with me all the time. Do you know the feeling you have when watching a scary movie when you know something terrible is just about to happen? And when it happens suddenly it scares the heck out of you? This was the state I was in when something heavy jumped onto my back. I let go of the hose, turned on my back, and kicked this thing off of me like a crazy man–like I was fighting off an alligator. Then I realized it was just one of the water-logged heavy pieces of wood I had thrown behind me.

This was a terrible feeling of terror and embarrassment. I’m serious; I was so scared, I wanted to crawl right back up into my mother’s womb. I was left wondering what the heck I was doing there. Why was I doing this? It was nuts!

It is impossibly-difficult times like this, and how you manage them, that contribute to the definition of your personal character and integrity. And I freely admit that staying down there to finish the sample was one of the most difficult challenges I have ever overcome. This was a total mission-impossible situation! After a moment to get myself refocused, I turned around and finished the sample hole to bedrock. I carefully shimmied back up the suction hose, coiling my airline as I went, to make sure it was not tangled in branches. When we cleaned up the sluice boxes, we were rewarded with several gem-quality diamonds, one which was quite large and handsome.

“I let go of the hose, turned on my back, and kicked this thing off of me like a crazy man!”

When I got back to camp that night, Alan was still sick in his cot. I did not hesitate to tell him of my experience. I also told him he was doing half the diving from then on, starting the next day, with or without jungle fever!

And that’s the way it went for the next twenty days or so. We completed four samples per day, with Alan doing half of the diving. Some days, the river was so high we had to tie off on branches of trees out in the middle of the river. We would take turns watching for trees being washed down the river, and would pull each other out by the airline every time this occurred, to keep from getting snagged by the trees and dragged down river.

The diving was extremely dangerous. Each time one of us went down, we did so knowing there was a definite possibility that we would not live through it. The only other option was to give up. But, we had originally agreed to do our best to overcome the difficult conditions. That’s how we got the job in the first place. We didn’t really have any other choice. I look back on it now and can enjoy the adventure. At the time, however, it was not any fun at all. It was crazy!

The diving was extremely dangerous. Each time one of us went down, we did so knowing there was a definite possibility that we would not live through it. The only other option was to give up. But, we had originally agreed to do our best to overcome the difficult conditions. That’s how we got the job in the first place. We didn’t really have any other choice. I look back on it now and can enjoy the adventure. At the time, however, it was not any fun at all. It was crazy!

The biggest problem was the lack of an air reserve tank on the dredge. Sometimes it would take as much as ten minutes to feel a way down through the submerged branches in the total darkness. We had to find a path. There was no easy, fast way to get back to the surface. Cutting the weight belt loose would probably be sure death. Not only that, but we would probably never recover the body! No reserve air tank meant almost no margin should the engine quit for any reason–which, luckily, it never did.

However, the heat from the compressor did melt the airline, causing it to blow off altogether when I was down on one dive. We run the airline around our neck and through our belt for safety. With no air reserve tank, we were able to hear the compressor working underwater by the vibrational sounds coming from the airline. I had just spent quite some time finding a path to the river bottom and started dredging gravel, when my air supply was abruptly cut off and I no longer heard the compressor noise from the airline. But the nozzle was still sucking. I stayed there for a few seconds trying to understand the problem and what to do, when suddenly my air supply returned and I heard the compressor noise again. I almost just kept on dredging, but decided after all to go up and see what had happened. When I got to the surface, Alan was holding the airline onto the compressor output with his bare hand. He got a pretty good burn out of it. An inexperienced underwater miner never would have known what to do. Alley saved my life. This is one of the reasons I seldom do these projects alone.

“He made his bow out of the core of a hardwood tree, using a machete to carve it exactly the way he wanted”

As we progressed with our sampling further down the river, the natives would move all the gear to new camps every three or four days. Some camps would be reconstructed out of already-existing structures. Other camps had to be built from scratch, using plastic sheeting for the roofing material.

Our main native guide was named Emilio. He was a real jungle man in every sense of the word. He walked with a limp because of an earlier airplane crash in which he was the sole survivor. His family hut had been hit by lightning several years before, and everyone in the hut was killed except Emilio. He was a real survivor! One night, he went hunting with our shotgun–which was only loaded with a single round of light bird shot. In the darkness of the jungle at three o’clock in the morning, Emilio snuck right up on a five-hundred pound female wild boar and shot it dead–right in the head. We had good meat for several days, and even the disgruntled cook cooperated with some excellent meals.

Our main native guide was named Emilio. He was a real jungle man in every sense of the word. He walked with a limp because of an earlier airplane crash in which he was the sole survivor. His family hut had been hit by lightning several years before, and everyone in the hut was killed except Emilio. He was a real survivor! One night, he went hunting with our shotgun–which was only loaded with a single round of light bird shot. In the darkness of the jungle at three o’clock in the morning, Emilio snuck right up on a five-hundred pound female wild boar and shot it dead–right in the head. We had good meat for several days, and even the disgruntled cook cooperated with some excellent meals.

Emilio taught us how to hunt with bow and arrows–mainly for fish. But, he was able to bring in a few chicken-like birds on several occasions. The meat was tough and stringy, but that was probably because of the cook. He made his bow out of the core of a hardwood tree, using a machete to carve it exactly the way he wanted. The arrows were made from the same hard material, using poison from snake venom on the tips for big game hunting. The natives did not have any modem weapons whatsoever, other than the shotgun we let them use while we were there.

Even Emilio refused to dive during the rains. And, our doing so considerably raised the natives’ evaluation of our physical abilities and bravery, even if we were greenhorns in the way of the jungle.

Each Indian we met was very skilled and uncanny in jungle survival. They could tell a boat was coming up the river three hours before it arrived by hearing the change in bird sounds. You will never find a harder bunch of workers anywhere.

The canoes we used were also carved

out of the trunks of hardwood trees. A skilled native takes about six months to make a good dugout canoe, which sells for about sixty dollars. Mostly, the canoes are paddled. But the more affluent natives do have outboard motors, which make the canoes go along at a pretty good clip. The natives are very skilled at driving the

canoes over top of submerged logs and through rapids. A lot of the time the boats were loaded so heavily that there was only about a half-inch of freeboard on each side. Yet, we never swamped a boat.

canoes over top of submerged logs and through rapids. A lot of the time the boats were loaded so heavily that there was only about a half-inch of freeboard on each side. Yet, we never swamped a boat.

The gold pans they used, called Beteas, are also carved out of huge logs. Several classifications of screens are used on top of the Beteas to classify material and screen for diamonds. The natives have a special way to quickly rotate the screens, which causes diamonds to move to the center of the screen where they are easily picked out. It is quite something to watch.

Many native miners only go after the diamonds. They know they only need to find about one or two diamonds a year to make it worth their while for the extra things they want. Otherwise, the jungle provides for all of the basic survival needs of the natives. They are quite self sufficient.

“I was running down the trail at full speed like a mad man out of control, swinging my hat about“

The natives received about two dollars a day in wages and were happy to get it up until the end of our project. We wanted to extend one more week to really finish the job right. However, the natives made it clear that no amount of money could sway them from going back to harvest their gardens on time.

While we were hauling our gear along the mile and a half-long trail to the landing strip, I was swarmed by African killer bees. It was terrifying! I heard them coming from quite some distance away. It sounded like a bus coming through the jungle. First, there were only a few bees around me, then a whole bunch. In panic, I was running down the trail at full speed like a mad man out of control, swinging my hat about. Then they were gone. I put my hat back on only to get stung right on top of the head. I felt completely spent. It was time to go home.

While we were hauling our gear along the mile and a half-long trail to the landing strip, I was swarmed by African killer bees. It was terrifying! I heard them coming from quite some distance away. It sounded like a bus coming through the jungle. First, there were only a few bees around me, then a whole bunch. In panic, I was running down the trail at full speed like a mad man out of control, swinging my hat about. Then they were gone. I put my hat back on only to get stung right on top of the head. I felt completely spent. It was time to go home.

When we returned to the base camp, we found out Sam had plenty of problems of his own. At least half his sampling crew had to be evacuated from the jungle due to an outbreak of malaria and yellow fever. When we arrived, he immediately needed our help to Griphoist the jeep out of a creek that it had crashed into. Apparently, the jeep had a problem jumping out of first gear while being driven down a hill. The lower gears needed to be used to keep the jeep from going too fast, because of the no-brakes situation. Sam was driving the jeep down a steep hill with four natives in the back. It popped out of gear and they made one mad roller-coaster ride to the bottom, only to smash right through their man-made bridge into the creek. Miraculously, no one was hurt and the jeep wasn’t wrecked. We managed to get the jeep back onto the trail and hightail it back to the base camp just as total darkness descended on the jungle. Sam looked at it as just another great adventure; just another day in the life of a jungle-man!

Our trip back from the jungle to Caracas was relatively uneventful, except that I was able to buy a nicely-cut diamond in Cuidad Bolivar for pennies on the dollar at U.S. prices. I presented this to my (ex) wife when I returned home and she was quite pleased to have it mounted on a ring.

Over all, our project was successful. We found diamonds, and we found some gold. We did exceptionally well considering the impossible conditions. The largest diamond located on the concession while we were there was over eight carats. But that came out of one of the test pits on Sam’s digging operation. We never found gravels deeper than three feet to bedrock, and there was very little oversized material to move by hand–other than submerged logs. The area would be a breeze to work in clear, slower water–like during the dry season. Everyone involved was impressed with our test results. We submitted a proposal to do a more extensive test/production project with more men and larger equipment, but internal politics within the company ultimately killed the program altogether.

I’ll say this: If we ever do go back, I guarantee it will not be during the rainy season. And we will have a cook who can find no better pleasure in life than to feed us well.

* The World Book Encyclopedia, 1987 Edition.

- More About Gold Prospecting

- More Gold Mining Adventures

- Schedule of Events

- Best-selling Books & DVD’s on this Subject